The London Film Festival never used to have awards, but in 2012 it's embraced the idea of a festival competition more than ever before, with three competition strands. So, just before my Top and Bottom 5's of the fest, and my final 4 reviews, here are my personal awards (good and bad) drawn from the 58 films I saw at the festival this year.

Best Director

Athina Rachel Tsangarai: The Capsule

Runner Up: Jacques Audiard: Rust and Bone

This is the first time in any of the awards posts I've ever done on the site that one of the main awards has gone to a short film, but in purely cinematic terms, as a piece of visual art and as a sustained vision, The Capsule was easily the most impressive directorial work I saw on show at the festival. Tsangarai draws inspiration from many other filmmakers (Lynch, Bunuel, Cronenberg), but also extends the personal style we saw in Attenberg. The visuals are stunning, but so are the pacing and mood, and it all adds up to a hypnotic piece of work.

My runner up is Jacques Audiard, whose Rust and Bone is probably my film of the year at this point. Audiard's depiction of violence, sex and depression is visceral, but he manages to combine it with some gorgeously stylised moments which, along with the brilliant performances, help convey the screenplay's complex set of mixed emotions. It's a brilliantly balanced piece of work.

Best Actor

Matthias Schoenaerts: Rust and Bone

Runner Up: Kim Kold: Teddy Bear

I had not seen, nor even heard the name of, Matthias Schoenaerts before sitting down to watch Rust and Bone, and his performance was perhaps the one that hit hardest during the festival. As Ali, Schoenaerts is never truly likeable, nor does he ever expect to or ask to be liked, but he lays the character so bare that we can't help but empathise with him. There's a crackling energy to the performance that draws us to Ali despite his flaws, and allows us to understand why Marion Cotillard's Stephanie is also drawn to him, and Schoenaerts also allows a few cracks to show in the tough front Ali puts up. It's a fantastically detailed piece of acting and often outright electrifying to watch.

Bodybuilder Kim Kold, my runner up, also plays an unconventional tough guy in Teddy Bear. Kold's passive, almost painfully sweet, gentle giant is one of the most purely endearing characters I've seen for some time and his small and subtle performance quietly, but hugely, impressive. I hope people see the film, maybe Kold's upcoming role in Fast 6 will encourage them.

Best Actress

Waad Mohammed: Wadjda

Runner Up: Shirley Henderson: Everyday

Waad Mohammed, just ten Wadjda was shot, had bigger challenges than simply being the lead, and in almost every shot, in her first film. The very act of starring in a film could have been dangerous for her, given that she and the rest of the cast were shooting in Saudi Arabia, where cinema itself is outlawed, under a female director who sometimes had to hide in the production's van and direct via radio, for fear that she'd be spotted. That's not why Waad Mohammed has won here. She's wonderful as Wadjda's central figure; a rebellious young Saudi girl who enters a Koran reading competition so she can buy the thing she wants most: a bike. Mohammed is a naturally engaging presence, and she creates a spunky, somewhat cheeky, entirely likeable and relateable character who we end up feeling deeply for, meaning that we engage with the character first and the film's politics second. I hope she gets the chance to make more films.

My runner up, Shirley Henderson, is much more experienced. I've been a fan of Henderson's for years, and it's great to see her frequent collaborator Michael Winterbottom give her a role so good as the one she has in Everyday. There's nothing showy in what Henderson does here, just an utterly convincing portrait of the day to day struggles, big and small, of a woman left to raise four kids while her husband is in prison. She can be a quirky presence, but here Henderson is simply real, and simply great.

Best Screenplay

Francois Ozon: In the House

Runner Up: Mamoru Hosoda / Satoko Okudera: Wolf Children

Francois Ozon has made many great films (don't argue this with me, we really will be here all day), but he may never have made one as interesting from a writing standpoint as In the House. The screenplay as as sharp and witty as you could hope for; Chabrolian in its barbed class commentary, and it's tense enough that the Hitchcock comparisons that have been thrown around are entirely warranted, but the real greatness of the writing here is how playful the script is. Ozon messes with us at every turn, almost begging us to guess his plot twists, then mocking us for trying and taking the plot in a direction we didn't guess. He plays with characterisation, making the bourgeois family his main character writes about thin enough characters that they could be fictional even within the film's universe, but rounded enough to hold our attention, and he plays with form, having characters offer commentary on the writing of a scene as it is unfolding. It's a dazzling piece of multilayered screenwriting.

Wolf Children is also a script with many layers, filtering its story of two children coming of age and the single mother struggling to raise them through a magical fantasy twist, through which Mamoru Hosoda and co writer Satoko Okudera bring their essential story home all the more powerfully.

Best Cinematography

Robbie Ryan: The Summit / Ginger and Rosa

Runner Up: Tobias Datum: Kiss of the Damned

I had many problems with Ginger and Rosa, but Robbie Ryan's cinematography was not one of them. Ryan's gauzy, dreamlike, lensing of much of the film gives it the feel of a half-remembered childhood (which fits the elliptical structure that undermines the storytelling so much), while his starker rendering of other scenes gives the film a sense of time and place, and of the two girls growing up too fast. It's a film so beautiful I wished it were better. Demonstrating his versatility, Ryan also acted as DP for the reconstruction scenes that made The Summit the one documentary I saw at the festival which really cried out to be seen at a cinema, the reconstructions have both staggering beauty and visceral immediacy, the mix serving the film brilliantly.

Tobias Datum's work on Kiss of the Damned is incredibly stylised; channeling the gaudy, somewhat cheesy, beauty of the films of exploitation directors like Jean Rollin. He captures the impossibly beautiful cast at their best, and, with director Xan Cassavettes, crafts a look that pays tribute to other filmmakers but also gives the film its own very particular feel.

Best Score/Soundtrack/Use of Music

Firework by Katy Perry: Used in Rust and Bone

Runner Up: Still Light by The Knife: Used in Jeff

The second time that Katy Perry's Firework is played in Rust and Bone, I almost cried. Shut up, you'd understand if you'd seen the film. The film completely changes the song for me, from a very lightweight pop record to something much closer to the inspirational tune Perry was clearly reaching for. The scene is beautiful, and the way Firework lifts what is a tiny victory for Marion Cotillard's character and makes us understand and share what it means to her is incredibly moving. It's an unlikely and brilliant soundtrack choice.

Jeff, the documentary about Jeffrey Dahmer, uses the dark and menacing electro of The Knife's brilliant third album, Silent Shout a couple of times during its dramatic scenes (which really don't work), but it's the choice of the album's closing track Still Light for the end credits that really stays with you, as it is much more effective than any of the reconstructions at conjuring the desperately creepy and disturbing nature of Dahmer's crimes, through Karin Dreijer Andersson's darkly pretty and haunting voice.

One to Watch

Chloe Pirrie: Shell

Runners Up: Caleb Landry-Jones: Antiviral / Sakura Ando: For Love's Sake / The Samurai That Night

Shell was one of the first films I saw at the festival this year, and while it has dropped out of my festival Top 5 (coming soon), Chloe Pirrie's leading performance has stayed with me. The restraint and subtlety with which she and co-star Joseph Mawle play the strangeness in the relationship between their father and daughter characters gives the film a fascination and a darkness that really pulls you in, and Pirrie impresses with the straightforward reality of her performance. We saw a lot of so called realism at the festival this year, and many of those performances felt very acted, Pirrie's doesn't. Shell will hopefully pull in an audience when it comes out, but at the very least it should act as a calling card for Pirrie, I'll be looking forward to what she does next.

Caleb Landry Jones is clearly a hugely versatile actor, and despite his extremely distinctive look I only realised on looking him up after Antiviral that I had already seen him as the weird brother of Ashley Bell's 'possession' victim in The Last Exorcism and as Banshee in X-Men First Class. He totally disappears again in Antiviral, anchoring the film with a withdrawn but mesmerising performance that signals an interesting young character actor.

Sakura Ando immediately impressed me in Sion Sono's brilliant Love Exposure, but her one two punch of small supporting roles in this year's LFF have convinced me that she's someone to be very excited about. As well as undoubted talent, Ando has something you can't buy or fake: presence. She appears in one scene in The Samurai That Night, but it's one of the most memorable, and she's only fourth lead in For Love's Sake, but when she appears you can't take your eyes off her. I can't wait to see more.

Right, that's enough of being nice. Here are some of the festival's low points.

Worst Actor

Gulshan Deviah: Peddlers

Runner Up: Jay Paulson: Black Rock

To be entirely fair to Gulshan Deviah, everyone in Peddlers is dreadful, and the film itself is a rampagingly awful, tonally broken, disaster. I don't think he ever had a shot at being good in it. That said... oh boy is he bad here. Playing a bad boy cop, Deviah is laughable; he's far too clean cut for the role, barely able to hide that charming movie star grin (pictured). The scenes in which he's meant to be most objectionable (like when he force feeds a woman cocaine) are unintentionally hilarious, because there's no sense of darkness in his performance, and frequently you feel like you're watching Deviah run through a scene and that the camera has simply been left running. Even funnier are the 'brooding' scenes as the character tries to hide his erectile dysfunction. You get the very real sense that Deviah is embarrassed even to suggest this about himself, and every scene feels incredibly awkwardly played. It's the most patently acted male performance I saw at the festival.

Jay Paulson doesn't fare much better in the considerably better film, Black Rock, in which he's the sole major weak link. It's a problem when the main antagonist in a horror film doesn't work, and Paulson doesn't. He starts out pretty wooden, but becomes hammier as each scene passes until he's off the deep end by the film's third act. It's an unbalancing performance in an otherwise pleasingly low key film.

Worst Actress

Christina Hendricks: Ginger and Rosa

Runner Up: Liv Tyler: Robot and Frank

Even leaving aside the fact that she is totally miscast as Elle Fanning's mother, Christina Hendricks is impossible to take seriously in Ginger and Rosa. In a film packed with American actors inexplicably cast as Brits, Hendricks is the one who struggles most. Her attempt at an English accent is hilariously awful, and sounds for all the world like it's coming out of another actress (who also can't do an English accent). What's really painful though is how apparent it is that Hendricks is working really hard at her accent, so hard in fact that she has completely forgotten to act. There's no inflection, no variation, just a flat, laughably overcooked, accent. That said, the conversation she has about pie is nearly worth the ticket price on its own.

From someone who is working far too hard to someone who is not working hard enough, to basically the same end. In Robot and Frank - a largely charming but already comprehensively overrated film - Liv Tyler appears to have recently woken from a coma and been wheeled on to set to play Frank Langella's daughter. Tyler's a variable actress, and this is one long off day, as she turns in a barely conscious, only occasionally inflected performance that threatened to send me to sleep.

Worst Score/Soundtrack/Use of Music

Michael Nyman: Everyday

Runner Up: Karan Kulkarni: Peddlers

Everyday is a hugely affecting and emotional film. I bought into everything; the process of the kids growing up without their dad, the wrenching feelings on both sides for their parents, the day to day struggles and feeling of imprisonment for Shirley Henderson's Karen and the love between her and John Simm's Ian. Score can augment those things, provided it does so with a little restraint, and that's where Michael Nyman went wrong here. Nyman and Michael Winterbottom simply slather Everyday in a gloopy score that essentially bellows at the audience about how they should be feeling at any given moment. It's a miracle that the film survives it, especially as it ends on a real crescendo of emotion, brutally undercut by the score blaring away.

Peddlers has a different sort of bad score. To go with the 'edgy' tone of the film Karan Kulkarni uses a lot of modern dance music... or some approximation thereof. The dance and club music in Peddlers is painfully generic, sounding like the stock music that TV shows used to be reduced to using when the characters went to a club but the budget wouldn't stretch to licencing any actual bands. It's utterly devoid of personality, and really doesn't fit with the film at all.

Oct 22, 2012

Oct 21, 2012

24FPS @ LFF 2012: Diary 19/10

The Central Park Five

Black Rock

Sleeper's Wake

Dir: Ken Burns / David MacMahon / Sarah Burns

It's been a year of crime and justice in the LFF documentary programme, and while The Central Park Five has garnered less attention than West of Memphis – just as it seems their case garnered little attention as the problems with it became clear it is, for me, a rather better film.

The case of the five men we we see and hear in the film (one, Antron McRay, didn't want to be on camera, so contributes only audio interviews) began in 1989, when they were just teenagers. A jogger was raped and beaten in the park and, in a familiar story, the five boys were picked up in an investigation that was rushed because of the urgency for the community to see justice being done. In two separate trials the boys were sentenced to between seven and fifteen years, all but one would have served their entire original sentence (Raymond Sanchez went back to prison after turning to selling drugs having been unable to find work after leaving prison) by the time that the problems in their case came to public attention.

Ken and Sarah Burns and David MacMahon examine the case in detail, looking both at the crime itself and the way it fit into the larger social picture of New York in 1989; especially in terms of the way race and class played a part in the arrest and conviction of the five boys. False confessions, as they often do, played a part in this miscarriage of justice, and the footage of the boys 'confessing' their 'crimes', thinking that this was what they needed to do: give the Police what they wanted so they could go home, is truly shocking.

The use of archive footage, both police footage and news coverage of the time (which, tellingly, seems to have no use for the presumption of innocence) is well used, and the new interviews with the boys - now all in their mid to late thirties - are equally good. The five are all very different, the most memorable interviews are with Korey Rice, who seems a touch slow and is the one you can imagine capitulating under interview and giving a false confession and with Raymond Sanchez, who clearly has a lot of anger still, which comes through with particular force when he talks about losing his faith around the time of the trial. The most incredible interview is one of the jurors in one of the original trials, where deliberations stretched on for ten days. Juror number five says that he was the only holdout who wanted to discuss the validity and believability of the confessions, but that after so long he simply wanted to go home, and changed his vote to run with the majority. It's an astonishing admission, and one that implies incredibly troubling things about any jury trial.

The Central Park Five brings an underexposed case into sharp focus, and asks pertinent and sometimes disturbing about the way justice - particularly American justice - is administered. It's an excellent film, and I'd expect to see it cropping up (retitled, naturally) on the BBC's Storyville some time soon.

★★★★

★★★★

Black Rock

Dir: Katie Aselton

One of the best things about the shake up in festival programming this year has been the Cult strand, which has, for the first time since I've been attending, brought more genre inflected cinema to the festival. Black Rock takes the survival horror genre, and, with the help of screenwriter Mark Duplass, filters it through the mumblecore style which has been an increasing presence in US independent cinema over the past six or seven years.

Sarah (Kate Bosworth), Lou (Lake Bell) and Abby (director and story writer Katie Aselton) were childhood friends, but Lou and Abby have grown apart since an incident six years before. Sarah wants the gang back together, and so invites each of them, without the other's knowledge, for a weekend on the island where they spent childhood summers, aiming to dig up the time capsule they buried 20 years ago. When they arrive they think they are the only people on Black Rock, but they run into three men recently returned from Afghanistan. When Abby begins flirting with Henry (Will Bouvier) things soon turn dangerous.

The thing I often find myself complaining about with horror cinema is the fact that characterisation is often very thin - too often thin to the point of total non-existence - or that if someone has bothered to flesh out the characters the result is that we immediately want them to die, slow and violently. That's not the case here. The film spends a measured first half hour establishing the three girls and their relationships. We get a sense of Abby as being very fragile, Lou the one who is up for confrontation, and more impetuous, and Sarah as the peacemaker. The dynamic between them is well drawn, and all three are sympathetic in their own ways. Abby, in particular, could easily have been grating, as a character who has held a grudge for six years, and who does complain rather a lot, but Aselton's performance is good, and makes her easy to empathise with. As you'd expect, given that this is a horror movie, dynamics shift, and all three leads cope well with this, particularly Aselton and Bell, who have the furthest distance to travel in the ways their characters change. Unfortunately not all of the performances are as good, nor all of the characterisations as successful. The antagonists being dishonourably discharged marines does smack of political point scoring, and it doesn't help that Jay Paulson, as Derek, turns in work that is alternately wooden and overegged.

The horror element of the film is well marshaled by Aselton (who scores one big jump scare with a moment that turns out to be ridiculously mundane), and she and Duplass serve up a few twists on horror convention that work quite nicely, such as finding a practical reason for Aselton and Bell to serve up what would otherwise be a gratuitous nude scene and not bowing to the tradition of the 'final girl'. The violence is relatively infrequent, and the film doesn't dwell in it - sorry gorehounds - but there are moments that feel really painful, and a couple of well realised practical gore effects (broken bones poking through skin always get to me). The main reason it works though, in spite of the slight weakness of the antagonists, is that you're invested in the three girls. I've said it so frequently, but a horror movie lives or dies on whether you care if the characters it puts in danger live or die. In this case I did.

Black Rock is not spectacularly original, nor is it a new horror classic, but it combines its initially disparate seeming genres effectively, is generally well acted, and is never less than engaging, certainly among the recent US horror crop, it stands out.

★★★

★★★

Sleeper's Wake

Dir: Barry Berk

We tend to see African films about the social and political situations either of the past or of the present, so I suppose that it's refreshing that Barry Berk's debut couldn't be further from that, instead taking a leap into genre territory; specifically a noirish thriller, albeit one that begins on a rather different footing, as a film about the grief of John (Lionel Newton) who wakes from a coma as the film opens, only to find that his wife and daughter have been killed in a car accident caused when he fell asleep at the wheel. To recover, John goes to a remote house in a coastal village, where he meets Roelf (Deon Lotz), who has also recently lost his wife. John gets close to Roelf's daughter Jackie (Jay Antsey), who seduces him; a dangerous secret to keep from the controlling Roelf.

I was rather enjoying Sleeper's Wake for about 80 of its 94 minutes, and then the ending happened. Before we get there though this is, on the face of it, an entertaining if somewhat trashy little noir, with shades of erotic thriller thrown in. It surprises you with what it is, because the first fifteen minutes play as a realistic drama about John trying to deal, with the help of his sister, with the grief and guilt of what happened to his wife and daughter. Lionel Newton's dazed performance proves adept at putting this across, and we expect this to be what the film is. The gear shift initially works well, with the unnamed coastal town John stays in exuding weirdness at every turn, so much so that I initially suspected that the local cop and even Jackie might simply be John's hallucinations, so strange is their behaviour. This feeling is also backed up by that same detachment in Newton's performance. The film keeps this feeling up well for a time, but as it becomes clear that this is not in fact the case, and that it is simply working through some standard thriller tropes, it becomes somewhat less interesting (though still a proficient and fun genre piece).

Jay Antsey is a fine femme fatale - you can see exactly why, despite her wildly changeable demeanour and her clearly mercenary aims, John is sucked in by her, and while he sometimes pushes the boat out into camp (even before the film goes off the deep end) Deon Lotz is an imposing and creepy presence as Roelf, his motives never quite clear.

However, with about fifteen minutes to go, Sleeper's Wake goes mental in a way so profoundly awful - let's just say, for those who have seen it, baboon - that not only was I trying to hold in derisive laughter, not only can the film not recover, but it undoes everything that went before, making it much less fun, much less intriguing because this stinkbomb of an ending was what it was leading up to. This is what Lionel Newton simply can't pull off; I buy him as shifty or conniving, as someone capable of calculated violence, but what we see here? Laughable. I wish I could actually discuss it in detail, go in to everything that is wrongheaded about the ending, tear strips off it without spoiling it totally, but I can't. All I can really say is that I can't remember the last time a film that, even if I didn't think it was any kind of classic, I had been enjoying unravelled so fast, so totally and so needlessly. It begins as a moderate success, but ends up a spectacular failure entirely of writer/director Barry Berk's making.

★★

★★

Labels:

2 stars,

3 Stars,

4 stars,

Documentary,

Festivals,

Horror,

LFF2012,

South Africa,

Thriller

Oct 19, 2012

24FPS @ LFF 2012: Diary 18/10

Punk

Dir: Jean-Stephane Sauvaire

Punk, in all honesty, isn't a terrible film, it's just one I feel like I've seen several hundred times before; one more in a long line of “I'm sixteen and angry at my Dad” movies. Looking as though it is set in the late 1970's among the French punk scene, and involving a couple of clashes between skinhead and anti fascist punks, the film it is most obviously comparable to is Shane Meadows' This is England, and that does Punk no favours at all.

Paul (Paul Bartel) is about sixteen, and lives with his Mother (Beatrice Dalle). He resents his absent Father, but has a few friends in the hardcore punk scenes and a Father figure at the gym he trains at. There's little in the way of story, and many trite scenes that we've seen in all of these films; the same fights with Mum, long anticipated confrontation with Dad, gang fights, fights with a girlfriend (Marie-Ange Casta, who shows up for about ten minutes total and contributes little of note aside from her fantastic breasts). None of it is notably terrible, but everything feels so rote, so seen it all before and so aimless.

Bartel and the rest of the non-professional cast do well enough, and Dalle remains a peculiarly fascinating presence, even in a role as thin as this, but I was never invested in Paul or his relationships.

Jean-Stephane Sauvaire is, apparently, yet another victim of the disease that makes its sufferers abandon technique in favour of 'realism'. In this case the most irksome feature is the fact that the film frequently looks like the focus puller fell asleep at his station. According to the LFF brochure the film is not set in the late 1970's as I thought. So when is it set? Sauvaire's design offers no clues, and if it is supposed to be contemporary why does nobody own a mobile phone? These are small details, but they all add up to create a satisfying picture of a world, and when they are missing that process is undermined.

I found Punk a wearing experience. I tired of its feedback loop of scenes of people shouting at each other between taking drugs, I found myself distinctly underwhelmed too by its desire to shock (a completely random scene featuring two transsexual hookers buying drugs) and annoyed by the level of cliché (yes, the obligatory traumatic haircut scene is here). However, the worst scene comes near the end, when Paul goes backstage at punk gig and get some spectacularly trite psych 101 advice from a singer, at which juncture Sauvaire may just as well put a flashing caption “THE POINT” on screen. It's a predictable and rather empty point, and getting there is a long and tedious process.

★★

★★

Dir: Sean Baker

The most frustrating experience as a critic is seeing a film you want to like, that you like parts of, but which doesn't manage to live up to its potential. On that note: Starlet.

Jane (Dree Hemingway) is a relatively new pornstar working in the San Fernando Valley. Furnishing her new rented room she picks up a large thermos at a yard sale, intending to use it as a vase. When she's first using the thermos, Jane discovers thousands of dollars in it. She spends some of the money and, feeling guilty about both that and the fact that Sadie (Besedka Johnson), the woman she bought the thermos from, clearly has no idea that there was money in it and won't take it back, Jane decides to befriend this irascible old woman.

In story terms, half of Starlet is excellent. The relationship between Sadie and Jane is original and well drawn by Baker's screenplay. It does go through all the familiar beats, as the suspicious Sadie slowly accepts Jane into her life and the sunny Jane works on brightening Sadie's life a little. Their interactions are funny, and the growing warmth that slowly seeps into Hemingway and Johnson's interactions with each other feels genuine.

For all that he does hit some familiar beats with his screenplay, Baker does have some more original touches, largely in what he doesn't include. Another film might have a forced heart to heart between Sadie and Jane about Jane's job, but it's never addressed (or judged), and the discussion about the money, which could hang over the film, never arises between them. This might feel like an oversight, but that scene could only really be a cliché, and I'm glad it's not there.

The two central performances are really the key. Johnson is prickly, irascible and often very funny while Hemingway is all sunshine and good intentions (so much so that after a while I forgot that she'd begun the film by, essentially, stealing from a woman in her eighties). Between them they make the half of the film that concentrates on this relationship both compelling and endearing.

The other side of the film, dealing with Jane's work and her friends in the porn industry (including her housemates Stella Maeve and James Ransone) is problematic in that it lacks that same appeal, has some serious issues with some of the performances, and suffers from a real tonal mismatch with the Jane/Sadie story. Worse is the decision to use hardcore insert shots during the scene that shows Jane going about her day job. I get that the film is going for gritty and realistic here, but it's undermined by the fact that it couldn't be more obvious that Dree Hemingway isn't the one performing these shots, and also by the fact that the scene feels completely gratuitous and out of place. It exists so that something can go wrong while Sadie is dogsitting for Jane, but there's no reason we need to see Jane at work, and certainly no reason for those hardcore shots, which will only limit the audience for a film that could otherwise have wider appeal. The tonal mismatch is stunning. The Jane/Sadie story is a film I would happily take my Mum to see, but the rest of the film totally and needlessly precludes that, and that's a real pity.

Starlet is Sean Baker's first feature, and you can tell. Visually the film is hamstrung by what is either technical incompetence or one of the worst artistic choices of the festival. Almost every other shot in the film, including every shot that takes place outside, is ridiculously overexposed, the light blown out to a distracting degree. Assuming the film was being correctly projected and that Baker and DP Radium Cheung aren't totally incompetent when it comes to lighting (and I suspect it was, and they're not, because the shots that aren't blown out are reasonably well composed) this is an inexplicable choice, and it nearly cripples the film.

I want to recommend Starlet, there are such good things in it, and Dree Hemingway makes a great impression and, I suspect, has as bright a future as her Mother, Mariel, but ultimately the film is so uneven. The good parts are well worth seeing, but really not enough reason to rush out and pay festival or cinema prices.

★★★

★★★

Love Story

Dir: Florian Habicht

Before our screening of Love Story began, co-writer/director/star Florian Habicht came in and told us about the genesis of the film, he'd seen a woman on the subway in New York and he had given her his email address so they could meet up again, but after waiting to hear from her, he realised he had given her an old address. He then spent several days walking around the place where he'd seen her, asking people if they'd seen a woman of her description, before giving up because in a city the size of New York it was ridiculous. He has, however, got a movie out of it. A movie this woman was watching with us yesterday.

Love Story is about the most generic title you could imagine, but Habicht's film is anything but generic. Boy (Habicht) meets girl holding a slice of cake (Masha Yakovenko). Boy misses his chance to see girl holding a slice of cake again. Boy finds girl (no longer holding a slice of cake) and from there, things get strange. Rather than just make a love story, Habicht appears to have his film largely written by vox pop. In what seem to be genuine interviews with real New Yorkers on the street (including one whose cab he abruptly jumps in) he elicits the twists and turns of his film. Some ideas are generic (looking for something to go wrong during his sex scene the first usable suggestion is that he loses his erection), others are unexpectedly original (interviewing a man who would likely place in New York's top 10 nerdiest he asks what kind of romantic gesture he should use to bring himself and the girl, Marsha, back together and gets a genuinely different and rather beautiful suggestion).

The blending and blurring of fact and fiction is cleverly done, and even when something is quite clearly staged (when it's clear that there are several angles he can choose from, for instance) it's incredibly easy to invest in because Habicht is such an endearing presence, and because he's established a (peculiar) sort of reality.

Love Story is extremely original, often funny and sometimes unexpectedly moving (a question about first love elicits an incredible story from a homeless man). I can see that some people will find the structure and the occasional preciousness annoying, but I found myself totally wrapped up, charmed by the story and impressed by the originality of the telling.

★★★★

Teddy Bear

Dir: Mads Matthiesen

The Teddy Bear of this film's title is a man, Dennis (Kim Kold); a gentle giant of a professional bodybuilder, living in Denmark with his elderly mother (Elsebeth Steentoft). Dennis' uncle has just come back from Thailand with a pretty young wife, and he suggests that his nephew make the same trip. Dennis takes the trip, but lies to his controlling mother about where he is going.

Teddy Bear is a wonderfully warm film, and that's largely down to the character of Dennis, and to Kim Kold's excellent performance. Kold is huge; clearly a real bodybuilder, and you can imagine him to be a scary guy to run into, but he makes Dennis totally disarming with a performance full of crippling shyness outside of the stage, and a simple, sweet, endearing nature. This doesn't mean that Dennis isn't complex. The relationship with his Mother is well drawn, and we get hints that while he's grown up as a man who is polite almost to a fault this relationship has also, whether passively or actively, prevented him from forming other relationships.

The film isn't exactly jam packed with surprises. The Thailand section of the film has some nice comic moments as Dennis tries to deal with aggressive advances of the prospective matches, but that part of the film really takes off when he goes to a gym and meets the widowed owner (Lamaiporn Sangmanee Hougaard). The relationship between her and Dennis is sweet and Kold and Hougaard, while a decidedly odd couple, do have an awkward kind of chemistry between them which makes for some laughs and some very touching moments (a shot of the two in bed together, fully clothed, combines the two to fine effect).

Both an unconventional romance and a coming of (middle) age story, Teddy Bear does both well. It's a real shame that Kim Kold's very specific look may restrict the roles he's offered in future, because his small but hugely expressive performance is the engine of this charming little film.

★★★

Jeff

Dir: Chris James Thompson

Titled The Jeffrey Dahmer Files in the LFF brochure, but going by Jeff on its title card, this documentary is a strange one by any title.

Director Thompson combines interviews with three key witnesses to the investigation of Dahmer; Detective Pat Kennedy, who took his confession; medical examiner Jeffrey Jentzen and Dahmer's neighbour Pamela Bass with archive TV footage and some oddly chosen reconstructions in which Dahmer (Andrew Swant) goes about first day to day activities then things related to the murders (which are never themselves depicted).

The construction is simply bizarre, and while the interviews – the one with extravagantly moustachioed Kennedy in particular – are riveting in what they reveal both about Dahmer and about the interviewees, you can't help but feel that only having three people talking, and having them constantly interrupted by the reconstructions is somewhat like looking through a keyhole at Mount Everest. The reconstructions just don't work, they tell us nothing that couldn't be better related by the interviews, and while they are well shot (on what looks like 16mm) they don't bolster our understanding of Dahmer at all, and feel rather aimless. I, and I suspect many other audience members, soon began greeting them with a sigh.

The parts of the story the film addresses are well told, and Chris James Thompson clearly knows the questions to ask. He's also made a stylish film, it looks striking in the reconstruction scenes, and the repeated use of Swedish electro band The Knife on the soundtrack is perfect, given their chilling, doomy music. It's just a shame that the film's brief seems so restricted, and thus it feels incomplete.

★★★

★★★

Labels:

2 stars,

2012 Releases,

3 Stars,

4 stars,

Crime,

Denmark,

Documentary,

Drama,

Festivals,

Film reviews,

France,

LFF2012,

Mini-Reviews

24FPS @ LFF 2012: Diary 17/10

In Another Country

Dir: Hong Sang-soo

Bayou Blue

Dir: Alix Lambert / David McMahon

I've always been interested, perhaps because it's very far from my experiences growing up in a very safe corner of the South East of England, in the darker side of life. We all are to a degree – why else is 90% of the news in our papers bad news? But even at that ratio, the papers can't contain all the horrible things that people do to one another, and such was the case when it came to a relatively recent series of serial killings of young men down in the bayou around the New Orleans area.

The Capsule [Short]

Dir: Athina Rachel Tsangarai

Boy Eating the Bird's Food

Dir: Ektoras Lygizos

Despite my long-standing fondness for South Korean cinema, I've never previously seen any films by one of its most prominent auteurs, Hong Sang-soo. I've often meant to see his films when they have come to previous LFF's, but never quite got around to it, but I knew I'd be seeing this one as soon as it was announced that he had cast Isabelle Huppert in the leading role.

In Another Country is really three short films more than it is a feature, with Huppert playing a different French woman alone in a small Korean town, interacting with the same small cast of characters (some of them in slightly different roles from piece to piece) in each of the shorts. In the first part Huppert is a famous film director, in the second she's a woman awaiting the arrival of her lover; a famous Korean director and in the third she's alone after her husband (who may be a director in this part, it's not quite clear) has left her for a younger Korean woman.

After, for the first time, finding her on autopilot in another of her four LFF films, Dormant Beauty, I was really hoping that In Another Country would find Huppert on form again, and it largely does. Huppert has a reputation as a stern and icy presence (and to be fair, few people do stern and icy as well), but here she's clearly having a lot of fun, putting on a flighty turn as the various incarnations of Anne enjoy flirtations with Korean men (her host/lover and a lifeguard) or ask inappropriate questions of Buddhist monks (“What is sex for you?”). There's a sense that Huppert is relishing the (slightly mannered) silliness of the script, and particularly of the many scenes in which the same dialogue is used, slightly tweaked to the different situation, scenes in which she seems just a small step away from winking at the audience. It's a very different Huppert than we're used to, and a welcome change. The other performances are equally good, particularly a turn full of nervous energy from the actor playing the lifeguard [IMDB lists actor names but not who plays who for this film], who is uproarious in the first section, when he writes a song for Anne (“Anne, Anne, this is a song for you”).

Hong Sang-soo's direction is as intentionally mannered as his script, with Anne's changing character indicated largely by her changing dress, along with a few other physical indicators – hairstyles, clothes – that serve to show that the other actors are playing different people in each short. As constructed as it is though, the film is always fun, with Hong using a few dream sequences and wry match cuts as much as he does the dialogue in order to get laughs.

In Another Country is insubstantial. It plays with narrative amusingly, if less assuredly than In the House does, and the performances are all perfectly pitched. It's a fun confection which has encouraged me to try some more of its director's work, but it could do with being a little more substantial.

★★★

★★★

Bayou Blue

Dir: Alix Lambert / David McMahon

I've always been interested, perhaps because it's very far from my experiences growing up in a very safe corner of the South East of England, in the darker side of life. We all are to a degree – why else is 90% of the news in our papers bad news? But even at that ratio, the papers can't contain all the horrible things that people do to one another, and such was the case when it came to a relatively recent series of serial killings of young men down in the bayou around the New Orleans area.

Between about 1998 and 2006 Ronald Dominique raped and murdered 23 men, most of them not yet out of their twenties, and for some reason, even regionally, the story was hardly picked up. This was one of the worst serial cases in US history, and it was all but unreported. Bayou Blue looks mostly at the later cases, the ones that led two local Sheriff's office detectives from two different parishes to finally catch Dominique. Directors Lambert and McMahon talk to the detectives, to victims families and, in one very striking interview, to a man who seems to have come very close to making the victim tally 24.

It's a fascinating case, and the story is told with assurance by the filmmakers and passion by the interviewees but, while there are some nice visuals of New Orleans bayou, the pressing issue is really that there's no reason this should be on a cinema screen rather than on TV. There is also something of a lack of focus, as if this reasonably short film has used up all its most interesting information in the initial hour, and has to overextend itself for the last twenty minutes, touching on things like media and coastal erosion, which have little to do with the case at the film's centre.

On the whole, Bayou Blue is well made, interesting, television, but I can't shake the sense that it is television.

★★★

★★★

Athina Rachel Tsangarai follows her striking feature debut Attenberg, unusually, with a 35 minute short. The film seems to take place at a castle in a completely deserted landscape, where six young women (including up and comer Isolda Dychauck and Clemence Posey) are put through a series of bizarre scenarios by a beautiful authority figure (Tsangarai's Attenberg star Ariane Labed). They lead Goats around on leashes, they dance as Labed sings A Horse with No Name, they make confessions and are punished in odd ways (one girl has her hair tied in a knot across her face). These things are also interspersed with a handful of animated sequences (such as a topless Daychuck pulling her chest open, her crudely animated guts spilling out).

The Capsule is a film awash in film knowledge and references, and it recalls everything from Lucille Hadzihalilovic's Innocence to Lynch, to Bunuel and even, in its frequent focus on bodily detail and strange movement, David Cronenberg. The meaning is elusive, but it hardly matters, because the imagery is so strange and riveting (thanks in part, it has to be noted, to the strange beauty of each of the actresses Tsangarai has cast). This gorgeous, baffling, film makes me sad that the distribution routes for shorts are so limited, because it's a hypnotising film, and one of the best I've seen at LFF this year.

★★★★★Boy Eating the Bird's Food

Dir: Ektoras Lygizos

I'm – annoyingly for a writer – at something of a loss for words. How do I even begin to go about itemising all that I hated about Boy Eating the Bird's Food? I wonder, in all honesty, if when he hoped we'd “enjoy the next 80 minutes of our lives” before the film, the producer was being ironic or facetious, because even if you see value in it (and I don't, and nor do I understand how anyone might), this is hardly an 'enjoyable' film.

The story is basically covered by the title. The lead character (Yorgos Karnavas) seems to be in his mid to late twenties and lives alone with a pet bird. He eats bird food and other things he finds, he stalks a girl who works in a hotel, visits an elderly man who lives beneath him and generally walks around a lot. NONE of his behaviour is given reason, little of it is shown to have consequences. Showing a character doing stuff, then expecting us to fill in every detail besides, is not a story and it certainly isn't a character study. It's merely stuff.

There is little on the technical side of the film to get excited about. It's largely shot in that irksome handheld 'look at me I can't hold the camera still so my film must be super realistic and smart' style that has become so prevalent of late and it's impossible to tell anything about the acting, because we know nothing about what this character is supposed to be like (we don't even know his name until it is randomly blurted out perhaps 15 minutes from the end of the film by an unseen character).

As well as being boring the film is also often disgusting, most notably in an utterly gratuitous scene, apparently staged for real, in which the main character jerks off in his hand before licking it clean, as well as in its apparent suggestion that if you stalk a girl long enough she'll eventually let you get intimate with her, and even pack up your dinner for you so you can take it away. As much as I was hating the film before, it really lost me half way in, when the main character danced to a song on Itunes, and chose Broder Daniel's Whirlwind, the theme tune of one of my favourite films of all time; Lukas Moodysson's Fucking Amal. Here's a tip for makers of future meaningless, character free, badly filmed pieces of cinematic dung like this: DO NOT remind me how much I'd rather be watching one of my favourite movies.

My parents have often asked me why I watch some of the films I choose to watch (horror, exploitation, etc etc). I'd really like to ask Ektoras Lygizos why he thinks we should watch this. Why for 80 minutes we should watch a character do nothing more than wander around, eat rotting food and occasionally stalk a girl. Why does he feel we should see this and learn nothing about him? What does he think we'll gain in insight? Does he expect us to make up a backstory, given that the only clue we get as to why the character is how he is is a brief and singularly unedifying phone call to his mother? What the hell is he trying to say with any of this? I don't care, at the end of the day. Boy Eating the Bird's Food is a waste of my time and even of the memory on the digital cameras used to shoot it. I'll be stunned if I see a worse film this year.

★

★

Labels:

1 Star,

3 Stars,

5 Stars,

Crime,

Festivals,

Film reviews,

Greece,

LFF2012,

Mini-Reviews,

South Korea,

Surreal

Oct 17, 2012

24FPS @ LFF 2012: Diary 16/10

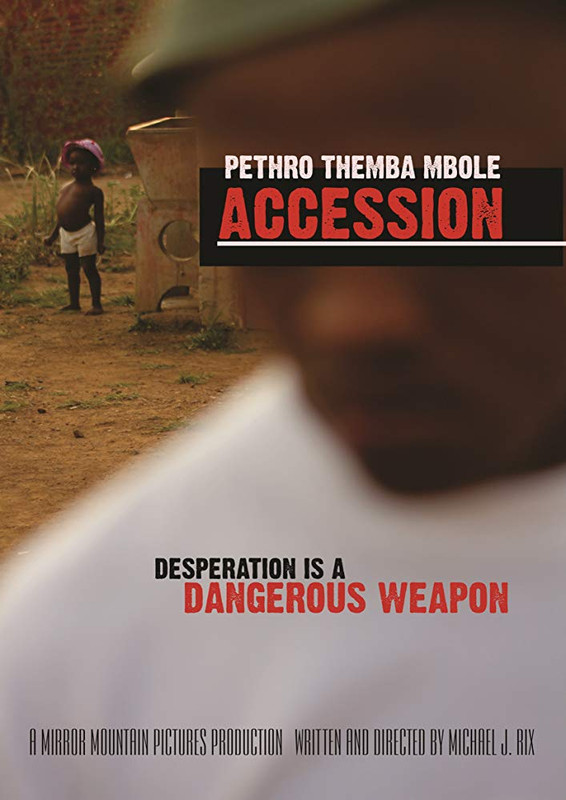

Accession

Dir: Michael J Rix

Everyday

Dir: Michael Winterbottom

Four

Dir:

Joshua Sanchez

Peddlers

Dir: Michael J Rix

This is probably the film I've had the most trouble getting a critical handle on during this year's festival. I found more than half of it quite painfully dull, but there are moments that are so profoundly, brutally shocking that as someone who finds extreme cinema fascinating I can't dismiss the film as a whole.

John (Pethro Themba Mbole) is unemployed, and spends his days wandering round his small South African town, drinking, chatting with friends he meets and having frequent, unprotected, sex with women he meets. One woman he encounters tells him that she has just been tested and is HIV positive, which makes John sure he must be too. Over lunch a friend says he's heard that sex with a virgin can cure HIV, thereafter John is on a mission.

For about 40 minutes of this 78 minute film all that happens is the handheld camera follows John as he walks from encounter to encounter. Director Rix hardly moves from close ups in this part of the film, almost the sole variation being that some shots are on the back of John's head and others on his face. It reminded me of Gus Van Sant's singularly unedifying Elephant. However, once John hears the gossip from his friend that sex with a virgin will cure HIV this same technique becomes much more interesting. Suddenly, because Pethro Themba Mbole's quiet performance still manages to communicate a lot, the walking, the following, take on an air of menace, because we know deep down that something very nasty is likely coming. This utterly changes the film in it's second half, and your heart is suddenly in your mouth.

There are two scenes that will keep most people from ever wanting to see Accession. I've seen a lot in my time as a movie fan. I watched Salo and happily ate dinner directly afterwards, and I count Cannibal Holocaust and Martyrs among my favourite films. Accession contains nothing as explicit as any of those films, but it does contain a scene which, by showing nothing, manages to be perhaps the most shocking single scene I can recall watching. It's also perhaps the best scene in the film, because Mbole's performance, the process of allowing John to decide to go forward in this hideous moment, is so articulate in its silence.

I would probably 'like' Accession much more as a 40 minute short, because even in the second half there is much that could be tightened, but for all its many problems, this is a film I can't dismiss.

★★★

★★★

Everyday

Dir: Michael Winterbottom

Michael Winterbottom has had a long and prolific career, but there is perhaps no more hit and miss filmmaker working today. He's capable of great things as both a dramatic (Butterfly Kiss, Jude) and comedic (24 Hour Party People, A Cock and Bull Story) director, but when he misses the mark the lows are catastrophically low (I Want You, With or Without You, Code 46).

This lack of consistency is a real concern when you consider that Winterbottom's new film; a drama about a family (Shirley Henderson and the four Kirk siblings) coping with the fact that the father (John Simm) is serving five years in prison, was shot in short bursts between other projects over five years. This was done, as it is being done over twelve years for Richard Linklater's upcoming Boyhood, so that we could see the actors, and particularly the children, grow and change in a completely organic way over the course of the film.

In this respect Everyday is an unequivocal success. The sense of the passage of time – which Winterbottom never flags up with captions -is totally organic. The children obviously change hugely, the eldest ageing from about 8 to 13 and the youngest from around 3 to 8, but we can also see the years adding up in Henderson and Simm (who begins to grey a bit towards the end of the film). It's also a remarkably consistent film given the production period, the untested child actors, and Winterbottom's aforementioned hit and miss filmography. Winterbottom, co-writer Lawrence Coriat and their cast have all managed to find and sustain a very strong tone of low key believability. This is indeed a story you can imagine is happening every day in many parts of the country.

Shirley Henderson has long been one of my favourite actresses, and it's great to see her get another film anchoring role several years after the strong, but almost totally unseen, Frozen. She's brilliant as Karen, giving us both a completely credible portrait of a Mother struggling to raise four kids by herself, to cope with the day to day challenges that come with that and a sense, without ever saying it that her husband Ian's sentence has put her in a kind of prison just as much as it has him. John Simm is equally effective as Ian, and between them he and Henderson feel like a credible couple that has been together for a long time, is enduring a hard time, but fundamentally still love each other. Both excel at the art of understatement, and say a lot with quite limited dialogue during the many scenes in which Karen and the kids visit Ian in prison, suggesting tension, love and the struggle to retain some sort of normality with a few looks and a few exchanges.

The kids aren't hugely stretched, and I had the feeling that most of the visit scenes were only loosely scripted, which, along with the fact that they are real life siblings, and so their relationships to each other are likely very much the same as they are here as in real life, would account for the beautifully unaffected performances that Winterbottom is able to draw from them.

Everyday is a fine film, but there were a couple of things that niggled at me in it. The first was just a question. How, given that she's only shown as working casually, does Karen maintain a reasonably nice house, support four kids, and frequently travel from Norwich to London to see Ian with at least two of those kids in tow? It's hardly a major issue, but it's odd, and when everything else feels so real it would make sense to have an idea of the financial pressures Ian's imprisonment must place on his family. The other issue is much more major, and that's Michael Nyman's score. For long periods the film unfolds without score, but when it comes on it feels as though Winterbottom and Nyman are dipping the film in raw sentimentality. It's especially damaging in the final shot, in which the score is almost begging you to feel something, while undermining that possibility.

Overall though, Everyday is a return to form for Winterbottom and essential viewing for fans of Henderson and Simm.

★★★

After

Lucia

Dir:

Michel Franco

It's

incredible, really, what people will do to each other. It would be

comforting to not believe the things we see in After Lucia happen, but we read about things that aren't far removed from it in the

papers almost every day.

Alejandra

(Tessa Ia) and her Father Roberto (Hernan Mendoza) have just moved to

Mexico City for a fresh start after the death of Alejandra's Mother,

Lucia, in a car accident. At a party with friends from her new

school, Alejandra is filmed having sex with a boy. The video soon

makes its way round the school, and makes Alejandra the target of a

disturbingly escalating campaign of bullying.

If

the content of After Lucia weren't disturbing enough (and, when a

birthday cake made of shit isn't the worst thing to happen to

Alejandra, you can be pretty sure it is) the way the characters react

– or rather fail to react – to it is perhaps more disquieting.

We get the feeling that both Alejandra and Roberto have been rendered

inert by Lucia's death, and perhaps even that Alejandra regards some

of what she's going through as 'punishment' as her Mother was

teaching her to drive when they crashed and she died. Tessa Ia's

performance may be extremely still and quiet, but there is still a

lot of turmoil evident behind her eyes, and it's clear from Hernan

Mendoza's equally detached performance that the reason Roberto isn't

seeing it is that he's really not seeing anything very clearly

through his grief.

The

film begins with a disturbingly real feel to it, and this helps as

the bullying escalates to a point that finally shocks Roberto out of

his stupor. While, happily, Michel Franco largely eschews the

shakycam stylings that have, somehow, become a shorthand for realism,

the performances of the schoolkids are extremely believable, and we

get a sense of the way that each act of bullying makes the next

escalation easier for them. The film does begin to strain credulity,

stopping just short of breaking point, in the climactic school trip.

The

problems in After Lucia are largely confined to the last twenty

minutes, in which the film takes a long expected but too late

executed shift in tone and genre. It's not a bad idea, nor are the

scenes themselves badly executed, but the shift feels like a bolted

on afterthought because it simply isn't given enough time to develop.

Leaving

this last section aside, After Lucia is a compelling and relevant

film, and well worth seeing for Tessa Ia's understatedly affecting

performance alone.

★★★

★★★

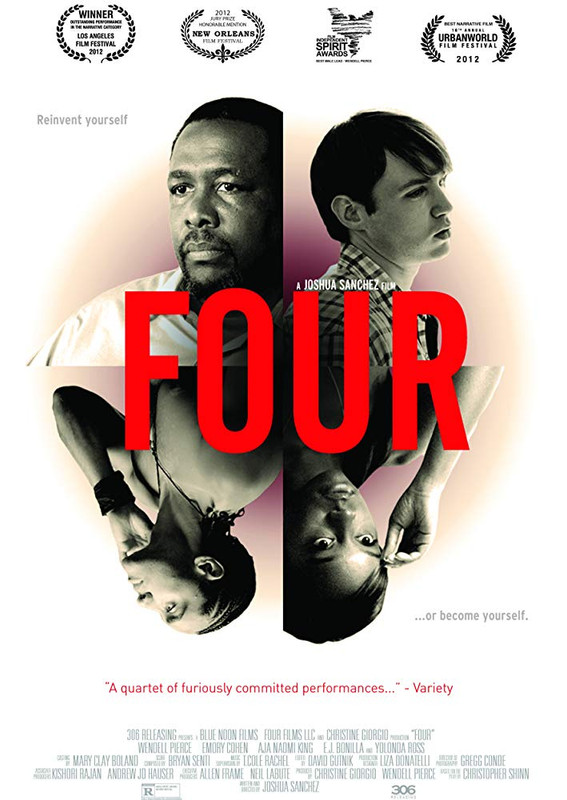

Four

Telling

two stories of four people on one July fourth, Four is perhaps more

mobile than a lot of stage adaptations, cutting between its two pairs

of characters as they move through the New York night, but it does

share some of the pitfalls of the filmed play.

Joe

(The Wire's Wendell Pierce) picks up a young man named June (Emory

Cohen) he has been talking to online for a date. Across town Joe's

daughter Abigayle (Aja Naomi King) sneaks out on her duties looking

after her mother for a date with Dexter (EJ Bonilla).

The

film largely centres on the exchanges between these four characters.

Joe and June talk about the fact that June hasn't come out, even

seems afraid of his desire as a boyfriend. Wendell Pierce is

fantastic in these scenes, allowing the subtext of Joe's own double

life (which we see vividly illustrated in one long shot at the end of

the film's second act) to bleed through, even as he forcefully tells

June that he should be fully out, that he should talk to Todd; a

friend he hasn't spoken to since Todd stepped out of the closet in

high school. It's actually a rather sad series of scenes, but the

point isn't beaten into you. Dexter and Abigayle's date night is a

little more typical. You might expect Dexter (who clearly is trying

to seduce Abi throughout) to come across as a bit sleazy, but EJ

Bonilla's sincere performance, and the strength of Abigayle's

character and Aja Naomi King's performance keep that from being the

case.

Neither

story is perfectly realised; Dexter and Abi's goes off the rails when

they get back to her place, and Joe and June's does sometimes feel

like it is reiterating the same (good) scene over and over again.

However, the film is held together, despite a slightly stagy feel to

the long and talky scenes, by impressively lush photography and the

strength of all four leading performances.

★★★

★★★

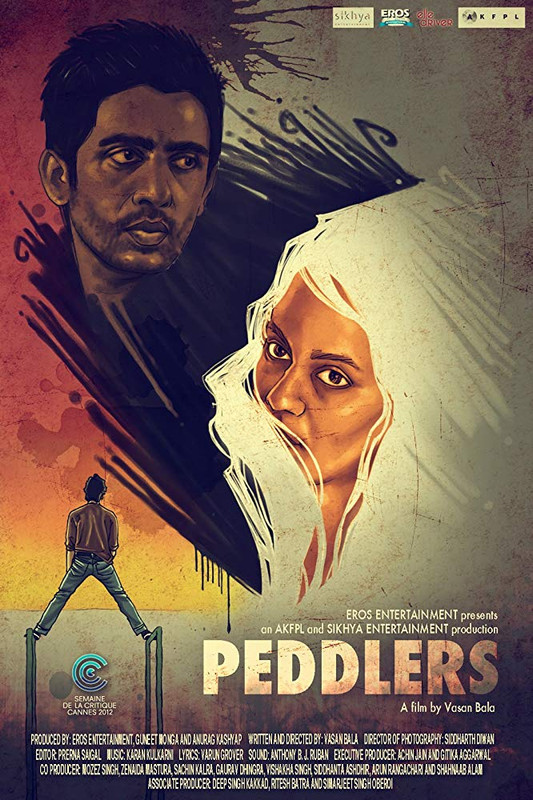

Peddlers

Dir: Vasan Bala

I've only ever seen one Indian film- Shekhar Kapur's debut Bandit Queen – before Peddlers. I've not been actively avoiding them, it's more that the Indian film industry is so vast, and most Bollywood films so impenetrable looking, that I've not really had a clue about a way into them.

Peddlers feels like an attempt to make a 'western' style film, with its 'gritty' subject matter and 'adult situations'. If Vasan Bala was trying here to make an American style thriller that might be a breakout hit then he has failed miserably.

The narrative has two strands. One is about a young man nicknamed Mac (Zachary Coffin), who is called upon to look after a drug mule named Bilkis (Kriti Malhotra), only to fall for her. The other story is about Ranjit (Gulshan Deviah); a cop who is going over the edge in both his work and his personal life as he tries to keep the shameful secret of his erectile dysfunction.

The Indian film industry was famously heavily restricted for a long time – even kissing was only allowed on screen less than 20 years ago – Perhaps Peddlers is the result of liberalisation, because it's a film that speaks to a writer and director with a desperate desire to be edgy and shocking, but with no concept of how to do it. In the roughly 40 minutes in which, across the first two acts, the film deals with Ranjit's erectile problems it does so either with breathtakingly misplaced earnestness or totally overblown shock moments (like the unintentionally hilarious moment in which he force feeds cocaine to a neighbour he's been flirting with and threatens her with arrest if she tells anyone his secret).

By contrast with the hilariously awful Ranjit story, Mac and Bilkis are just a bit dull. We know Mac is in love with Bilkis because he says so, but there's no sense of it in any connection between the characters or in the performances. The film tries to beat emotional involvement out of you with the revelation that Bilkis has cancer, but it doesn't work because it never seems to effect her. There are similar problems with the drug mule side of Bilkis storyline, which is set up, but never seems to go anywhere. The best thing I can really say for this part of the film is that Kriti Malhotra is beautiful.

The third act of the film lurches even further off the rails, finally bringing the stories together in a way so contrived and so misconceived that I wasn't sure whether I should laugh or cry at the ineptitude on display. Again, Vasan Bala goes for brutal and shocking, but has no clue how to do it, and so ends up with unintentional comedy. Peddlers is a terrible film. It's hurt by an abysmal screenplay, performances that suffer from being in a seemingly random mix of barely inflected English and Indian, and a complete miscalculation of tone. It is sometimes quite funny though.

★

★

Labels:

1 Star,

3 Stars,

Film reviews,

India,

LFF2012,

Mexico,

Mini-Reviews

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)