Dir: Pete Docter / Ronnie Del Carmen

Pixar's early run was almost perfect. A Bug's Life might not have hit the heights of Toy Story but otherwise, until the middling Cars, they had an astonishing hit rate. Lately, though, returns have seemed to be diminishing, with Cars 2, Monsters University and Brave all disappointing, artistically if not commercially. Meanwhile, Disney is in the midst of what appears to be an animation renaissance with Frozen, their best film since Beauty and the Beast, rapturously received by critics, the biggest animated film ever at the box office and a genuine cultural phenomenon. Inside Out, it could be said, has some work to do in re-establishing Pixar's reputation.

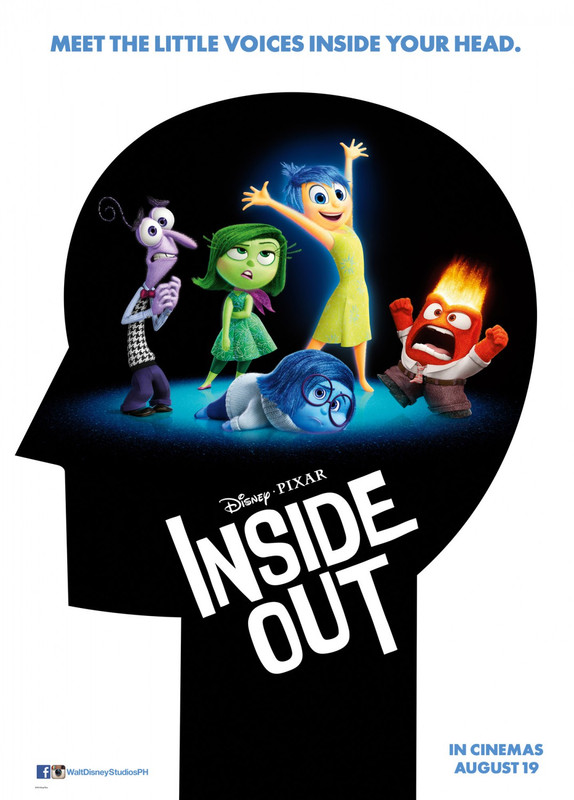

The film is set largely inside the mind of Riley (Kaitlyn Dias), an 11-year-old girl. In headquarters, her emotions – Joy (Amy Pohler), Sadness (Phyllis Smith), Anger (Lewis Black), Fear (Bill Hader) and Disgust (Mindy Kaling) take turns at the controls, building Riley's memories and thus her personality. Riley is a happy little girl until her parents (Diane Lane and Kyle MacLachlan) move from Minnesota to San Francisco. There, Joy becomes frustrated when a sad memory is due to become part of the core of Riley's personality, and there is an accident in which Joy, Sadness and all of Riley's most important memories are cast out of Headquarters. Without two key emotions, Riley isn't her usual self, and Joy and Sadness must get back before something terrible happens.

In any film, the audience needs information to allow them to enter the world of the story. Who are these characters that we're about to spend the next 100 minutes with, what is the context in which they exist, what, if any, are the technical details we need to understand in order to access the film's world? There are many ways and means of doing this. For instance, in Inception, we have Ellen Page's character, whose every line seems to be “what's that” or “how does that work?” This is the kind of exposition I hate; characters spewing raw (usually indigestible) information at each other.

Inside Out completely sets up its uniquely imagined world, its technicalities and its rules within the first ten minutes which, as in Pixar's earlier Up, seem to function almost as a short film to set up the tone of the next 90 minutes. Happily, it never feels like you are being spoonfed information. As we watch Riley grow from a newborn who initially knows only Joy (though she is joined by Sadness after 33 seconds) to an 11-year-old girl with personality islands devoted to Hockey, Family and, adorably, being a goofball, the film communicates emotion as much as it does information. Part of this may have worked on me because the early moments made me think of my nephews (22 months and 5 months), but the film never tugs the heartstrings in a way that feels crudely calculated.

Pixar have made mini-masterpieces before. Up only intermittently hits the emotional heights of its opening sequence in the rest of the film, and Wall-E feels like two separate films, never recovering after Wall-E boards the spaceship and humans enter the film. This isn't the case with Inside Out, which manages to sustain the momentum of its opening. With dazzling inventiveness, Pete Docter, Ronnie DelCarmen and Pixar's rightly legendary story department find a series of relatable metaphors to dramatise the inner workings of the mind, as well as to create a landscape that lends itself to a tricky adventure for Joy and Sadness to go on. There is an especially good joke involving dream production, which works like a movie studio and where we see posters for previous attractions such as 'I'm Falling Into a Pit'. Some of the film's best moments come in these relatable, seemingly throwaway, gags. One that struck close to home for me was towards the end when we get a glimpse into a 12-year-old boy's brain when Riley speaks to him. From time to time I'm still that kid. These are the little joys of this film, but every one of them adds to the richness of its world.

Other seemingly throwaway jokes actually run deeper. The team clearing out fading memories and sending them to a deep part of Riley's brain where they will lie forgotten is a masterstroke, especially in Joy's reaction to them; she treasures every little moment, even if Riley doesn't need it, more Riley's parent than her emotion at this moment. Of course, this sequence also has some lovely gags, such as an explanation of why a random pop culture memory can often pop into your head unbidden.

We see this dual purpose in almost everything in Inside Out. When Riley's personality islands crumble, for instance when her goofball side collapses, it is desperately sad because we understand what it means for Riley, but it also adds to the adventure of Joy and Sadness' quest, cutting off a route back to Headquarters. This comes across especially well with the character of Riley's imaginary friend Bing Bong (Richard Kind), who still roams free in her memory, despite the fact she hasn't thought about him in a long time (another idea that rings very true). Bing Bong is a funny character and a cute piece of design, but for adults, there is another side to his character. Similarly to the toys of the Toy Story trilogy, we know that redundancy is an inevitability for Bing Bong, just as it was for any imaginary friends we may have had as children. This runs right through Bing Bong's role, coming to a head in one of Pixar's most beautifully tragic scenes with one of several lines that made me tear up.

We see this dual purpose in almost everything in Inside Out. When Riley's personality islands crumble, for instance when her goofball side collapses, it is desperately sad because we understand what it means for Riley, but it also adds to the adventure of Joy and Sadness' quest, cutting off a route back to Headquarters. This comes across especially well with the character of Riley's imaginary friend Bing Bong (Richard Kind), who still roams free in her memory, despite the fact she hasn't thought about him in a long time (another idea that rings very true). Bing Bong is a funny character and a cute piece of design, but for adults, there is another side to his character. Similarly to the toys of the Toy Story trilogy, we know that redundancy is an inevitability for Bing Bong, just as it was for any imaginary friends we may have had as children. This runs right through Bing Bong's role, coming to a head in one of Pixar's most beautifully tragic scenes with one of several lines that made me tear up.

The animation is beautiful throughout, clearly delineating between the more stylised world of the working of Riley's mind, which is all brightly coloured balls of memory and jagged, forbidding levels of subconscious and the more realistically rendered world of San Francisco, which seems to become duller and more drab as the film goes on, to reflect Riley's growing dissatisfaction with the place. We don't spend a huge amount of screen time outside Riley's mind, but what we do see is enough to have us invest in a set of family relationships that ring true and to come to like both Riley and her parents. Animation wise the standout moment sees Joy, Sadness, and Bing Bong, running to catch Riley's train of thought, take a shortcut through abstract thought. In there they are broken down, becoming ever simpler until they are just 2D shapes. It's a moment more from Looney Tunes tradition (specifically Chuck Jones' glorious Duck Amuck) than Disney.

For all its humour, all its invention and all its adventure Inside Out comes down to emotion, and to the realisation that it's just not realistic to think that all of our memories and experiences can be, or even should be, happy. For much of the film, Joy tries to shunt Sadness aside and to keep her out of Riley's experience. This is a coming of age film, and its real moment of growing up, for Joy and Riley alike, comes when it is accepted that Sadness is an important part of Riley's experience and that her memories needn't always be defined by a single emotion. It's a rather profound truth to find in what is, on its face, a children's film, and it is beautifully and subtly articulated.

Inside Out is all too rare a film; as intelligent as it is entertaining, as moving as it is funny. It's more than a return to vintage form for Pixar, it's one of their very best films.

★★★★★

★★★★★

No comments:

Post a Comment