Dir: Francois Ozon

The new film by Francois Ozon is always an occasion I await with great anticipation, and it has become a tradition that he brings them to LFF each year. After a run of quality all but unprecedented among working directors (a parade of 4 and 5 star films broken only by his English language début, Angel) Ozon hit his first major stumble with Jeune et Jolie, but seemed to have regained momentum with his last film, The New Girlfriend. Frantz, disappointingly, represents another backward step.

The auteur theory can be overapplied, but if it were written to describe any modern director then it is Ozon. One of the most versatile directors of his generation, Ozon can change mood, subject and genre wildly between films, but his identity, his favoured images and ideas, recur like a fingerprint. An Ozon film is different from every other Ozon film, but you would never be in any doubt as to who directed it. Until now.

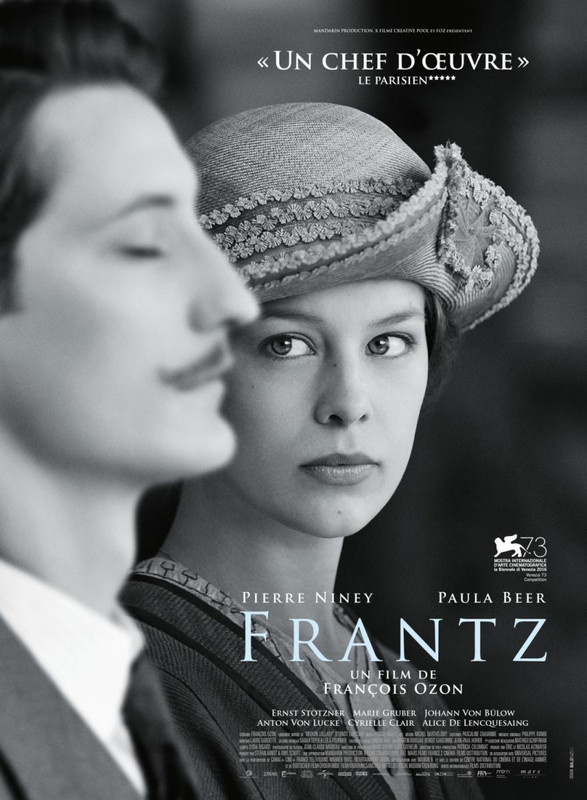

Frantz, as ever, finds its director in new territory. Set in the aftermath of World War One, it begins in a small German town. Visiting the grave of her fiancée Frantz, Anna (Paula Beer) finds flowers that were not left by her. The next day she discovers that they were placed by a French soldier, Adrien (Pierre Niney), who says that he was a friend of Frantz' before the war. Frantz' family begin to rely on Adrien, who reminds them of their son and Anna's feelings for the Frenchman begin to grow, but Adrien has a secret that changes those relationships again.

Perhaps the biggest change from his previous films is that here the colour obsessed Ozon shoots almost entirely in black and white. This is supposed to plug us into the period in which the film is set, but it looks too clean for that to come off. More disappointing still is the limited use of colour. The slightly faded colours are beautiful, but the moments that Ozon chooses to use them couldn't be more obvious or groan-inducingly literal. Yes, he uses colour to reflect the characters emotional states, but it's so basic an idea that the execution feels more like that of a clumsy film student than one of modern cinema's greats. This is only exacerbated by the awful final shot; a piece of sentimentality straight out of the ending of (500) Days of Summer, and maybe the single worst scene Ozon has put on screen.

The force of personality that Ozon usually brings to his films has gone missing here. The film's forward looking message, the German and Paris scenes both laced with warnings of the coming Second World War, feels less of this filmmaker than it does like Ozon trying to do The White Ribbon; Haneke on happy pills perhaps. But Ozon can't pull off the doomy sense of the weight of destiny that Haneke delivered. The happy pills aren't working either, here Ozon has none of his usual playfulness and while he's also effective in severe, dramatic form, Frantz also misses this target.

In just about every way, Frantz is a weightless film. The budding romance between Adrien – Niney looking unsure and out of place, like a kid playing dress up in a stick on moustache – and Anna is unconvincing, even before Adrien's entirely expected revelation comes out, after that point, with such a tenuous connection established between the characters, it becomes almost laughable, fatally undermining the film's Paris set third act. This might have worked in the 1930s, in the Lubitsch film in which Ozon based his screenplay, but the whether it's the non-existent chemistry between Beer and Niney or the fact that the screenplay gives them too little to hang the relationship story on, something about it just doesn't work here.

There are a couple of positives to take from Frantz. German actress Paula Beer is a find; Ozon gives her less to work with than his usual rich female roles, but she gives a strong performance, much of it in a second language (Niney struggles more with his German than Beer does with her French). The best performances in the film, however, come from Ernst Stotzner and Marie Gruber as Frantz' parents, both broken by grief, but cheered by the little glimpses of their son that Adrien offers them. There are also a few standout scenes: Anna inventing a letter from Adrien, to avoid telling Frantz' parents the real truth; Anna sitting, deeply uncomfortable, as the Marseilles is sung in a Paris bar, but these are scattered moments in a near two hour film, and good as they are in isolation they can't make it knit together as an effective whole.

If Frantz isn't Ozon's worst film it's certainly his most anonymous. This doesn't feel like a filmmaker changing direction, it feels like he's dropped the map and got lost. Worse than all this is that, for the first time in an Ozon film I didn't like, I can't see what drew him to tell this story, what he was going for. For all its faults, Jeune et Jolie had something interesting at its core, it didn't work, but it still gave me something to think about and discuss. Frantz doesn't even have that, it's a pure misfire, not even very interesting in its failure.

★★

★★

No comments:

Post a Comment