Rewind

Dir: Sasha Joseph Neulinger

Film serves many functions in our lives. It can be pure escapism and entertainment, but it can also serve as an archive; a document of what we are thinking and feeling in a given moment, or as evidence of another kind.

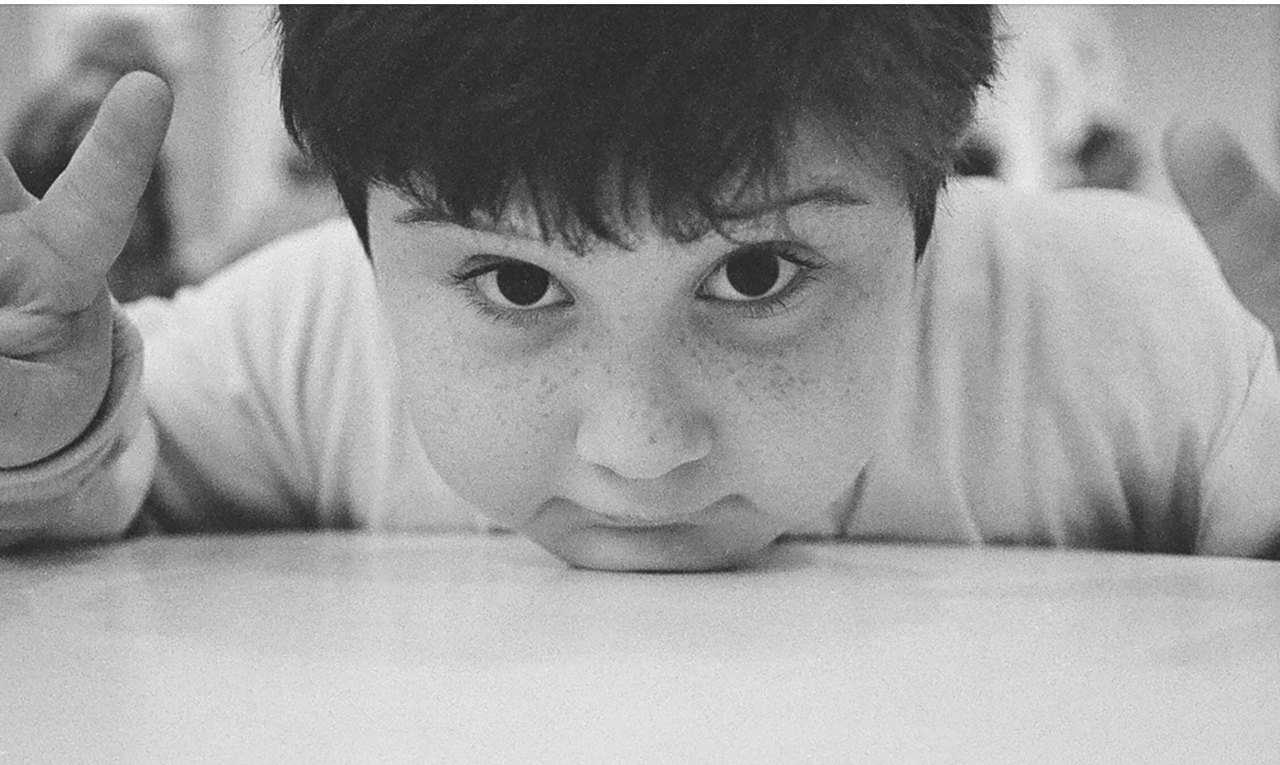

Sasha Neulinger’s directorial debut is a bravely personal film, looking back on the sexual abuse that came from within his family towards both him and his younger sister, when they were each as young as three years old. Through a patchwork of archive footage taken by his filmmaker father and present day documentary and interview footage, “It’s a puzzle made from my life”, says Neulinger, as he opens the film in which he combs through his childhood to recall and to contextualise the abuse, focusing on how it seems to be passed down like a virus.

The archive footage, at first glance, is much like that which any family who had a video camera in the 90s might have taken; family gatherings, parties, trips to the zoo the kids playing outside. There is a dark side though, and it’s present from the off, as we see a roughly 9-year-old Sasha introduce his “Shit diaries” direct to camera. What emerges as the pieces of the puzzle form a full picture is a jagged image of a disturbed boy whose initially sunny and open nature was blown apart early in his life, leaving a child who couldn’t express his emotions except in anger and acting out.

Today’s Sasha is markedly different, but there is still a raw feeling to the film as it is plain that revisiting these times, even if it is eventually cathartic, is deeply difficult for him. In one scene, as his father describes his own childhood abuse from a brother who would grow up to also victimise Sasha, we can see the director in background of his shot, clearly shocked, moved and holding back tears. In another moment that speaks of deep connection, both as family and survivors, Sasha gives his sister Beckah a long hug following her interview. It’s this long thread of shared experience the runs throughout the film that is, in many ways, its most shocking aspect.

Rewind is, obviously given its subject matter, a challenging watch. Moments that find Neulinger looking through his old therapy records with his doctor, looking back at drawings that graphically - if largely metaphorically - describe his abuse are especially hard to stomach. Yet there are also moments of grace, not least the one in which, in archive footage, Sahsa reveals that he’s changing his surname to Neulinger.

The form of Rewind is fairly familiar, not least from the acclaimed Capturing the Friedmans, but coming from a first person point of view gives the way that the stitching of this patchwork of footage a somewhat different power to that of the earlier film. This case has already made positive change, but this film will bring it to a wider audience, particularly if it is picked up by something like the BBC’s Storyville series, which is the sort of distribution that might suit it best. That would allow Neulinger’s campaigning, but never brow beating, film to get out and perhaps make a wider difference.

★★★½

The Miracle of the Sargasso Sea

Dir: Syllas Tzoumerkas

The name may not be entirely accurate anymore, but after more than a decade it still feels as though the Greek ‘weird wave’ is surfing in the wake of Yorgos Lanthimos. While he has managed to transfer his talents, with his peculiar tone largely intact, to higher profile and even prestige projects, many other filmmakers have remained at home, ploughing a similarly strange furrow. Syllas Tzoumerkas was last seen at LFF with the awful A Blast, his latest film has a little more going for it, but suffers from many of the same issues.

For the first half, Tzoumerkas and co-writer Youla Boudali set their pieces. Elizabeth was a cop in Athens but in the opening sequence we see her asked to join other officers in lying about planted evidence. 10 years later, Elizabeth (Angeliki Papoulia) is living with her now teenage son Dimitris (Christian Culbida). Elizabeth the chief of police in their small town. She’s a drunk, a casual and sometimes open drug user, constantly berating the officers below her and not above her own corrupt actions. Other strands involve the rest of the people in town, from club singer Manolis (Hristos Passalis) and his sister Rita (Boudali), who have a fractious relationship with him doing most of the caring for their mother, who has alzheimer's to, among others, Elizabeth’s married lover Vassilis (Argyris Xafis), local DA Andreas (Laertis Malkotsis) and Andreas’ mute brother Michalis (Thanasis Dovris).

There are a lot of tangled strands set up here, but only Rita’s story grabs much attention. This is where the film suggests the most depth, with her job cleaning a church and the various biblical visions we see through her story promising something with a powerful undertone but, as with many other things it sets up, the film never really delivers on this. The visions seem just to be there, perhaps someone more well versed in Greek Orthodox doctrine could unfold something specific from them, but for me they ended up feeling empty. That’s less true of Youla Boudali’s performance as Rita though. We get, at the very least, a sense of trauma and of something rather dark lurking underneath her relationship with Manolis (a slickly dislikeable turn from Passalis).

The rest of the film is far less interesting. Elizabeth’s story starts intriguingly enough, leaving some ambiguity about how she reacted to the bribe in the opening sequence, but once we find her a decade later, Angelikki Papoulia’s performance is disappointingly lacking in any shading. Her constant anger, her lack of any subtlety in her performance outside the film’s bookending scenes becomes wearing very quickly. Having a heroine who isn’t someone we would usually root for is fine, but the screenplay allows Papoulia little to work with in terms of contextualising Elizabeth’s rage and keeps her at such a constant boil that her every scene feels like a reiteration of the last.

As the second half of the film begins to use a murder mystery - the solution to which is hardly a surprise - to unpick the strands the first half set up, the extreme dark secrets that lie under the quietness of this town feel, for all the deadening and pointless explicitness with which Tzoumerkas shows them, somehow inevitable. He’s clearly going for shock value but a decade of films from Greece that have used many of the same ingredients, along with the fact we only really know and care about one of the characters involved, means the effect is considerably blunted.

There are flashes of interest here, notably in Youla Boudali and Hristos Passalis’ performances (he is especially good as he seemingly snaps after a performance, and begins berating the home town crowd from the stage) and in the various biblical overtones that surround their story. However, Tzoumerkas and Boudali’s screenplay is far too unfocused and, in other areas, too one note, to sustain that interest for the two hours the film runs.

★★

The Miracle of the Sargasso Sea

Dir: Syllas Tzoumerkas

The name may not be entirely accurate anymore, but after more than a decade it still feels as though the Greek ‘weird wave’ is surfing in the wake of Yorgos Lanthimos. While he has managed to transfer his talents, with his peculiar tone largely intact, to higher profile and even prestige projects, many other filmmakers have remained at home, ploughing a similarly strange furrow. Syllas Tzoumerkas was last seen at LFF with the awful A Blast, his latest film has a little more going for it, but suffers from many of the same issues.

For the first half, Tzoumerkas and co-writer Youla Boudali set their pieces. Elizabeth was a cop in Athens but in the opening sequence we see her asked to join other officers in lying about planted evidence. 10 years later, Elizabeth (Angeliki Papoulia) is living with her now teenage son Dimitris (Christian Culbida). Elizabeth the chief of police in their small town. She’s a drunk, a casual and sometimes open drug user, constantly berating the officers below her and not above her own corrupt actions. Other strands involve the rest of the people in town, from club singer Manolis (Hristos Passalis) and his sister Rita (Boudali), who have a fractious relationship with him doing most of the caring for their mother, who has alzheimer's to, among others, Elizabeth’s married lover Vassilis (Argyris Xafis), local DA Andreas (Laertis Malkotsis) and Andreas’ mute brother Michalis (Thanasis Dovris).

There are a lot of tangled strands set up here, but only Rita’s story grabs much attention. This is where the film suggests the most depth, with her job cleaning a church and the various biblical visions we see through her story promising something with a powerful undertone but, as with many other things it sets up, the film never really delivers on this. The visions seem just to be there, perhaps someone more well versed in Greek Orthodox doctrine could unfold something specific from them, but for me they ended up feeling empty. That’s less true of Youla Boudali’s performance as Rita though. We get, at the very least, a sense of trauma and of something rather dark lurking underneath her relationship with Manolis (a slickly dislikeable turn from Passalis).

The rest of the film is far less interesting. Elizabeth’s story starts intriguingly enough, leaving some ambiguity about how she reacted to the bribe in the opening sequence, but once we find her a decade later, Angelikki Papoulia’s performance is disappointingly lacking in any shading. Her constant anger, her lack of any subtlety in her performance outside the film’s bookending scenes becomes wearing very quickly. Having a heroine who isn’t someone we would usually root for is fine, but the screenplay allows Papoulia little to work with in terms of contextualising Elizabeth’s rage and keeps her at such a constant boil that her every scene feels like a reiteration of the last.

As the second half of the film begins to use a murder mystery - the solution to which is hardly a surprise - to unpick the strands the first half set up, the extreme dark secrets that lie under the quietness of this town feel, for all the deadening and pointless explicitness with which Tzoumerkas shows them, somehow inevitable. He’s clearly going for shock value but a decade of films from Greece that have used many of the same ingredients, along with the fact we only really know and care about one of the characters involved, means the effect is considerably blunted.

There are flashes of interest here, notably in Youla Boudali and Hristos Passalis’ performances (he is especially good as he seemingly snaps after a performance, and begins berating the home town crowd from the stage) and in the various biblical overtones that surround their story. However, Tzoumerkas and Boudali’s screenplay is far too unfocused and, in other areas, too one note, to sustain that interest for the two hours the film runs.

★★

A Thief’s Daughter

Dir: Belén Funes

Late on in A Thief’s Daughter, Sara (Greta Fernández) is asked why she can’t just forget about her Dad “I carry him in my face”, she says. There’s a push and pull in that moment that is felt throughout Belén Funes excellent feature debut.

Sara is 22, she’s scraping away in a variety of menial jobs, trying to make ends meet for herself and her baby son, while also trying to win custody of her seven year old half brother Martin. Her father (played by her real life father Eduard Fernández) has just got out of prison and she clearly craves a family connection, while also being aware that being around him may not be good either for her or for Martin.

This isn’t a film of big dramas, confrontations are small and brief, grounded in the same reality as the rest of the film. Funes constructs a beautifully observed film, her camera more often feeling like a third person in the room more than it does something imposing structure. With that said though, she also has an incredibly economical style, often unfolding whole swathes of backstory without a word. In one especially impactful moment Sara is washing up after celebrating Martin’s first communion, she gets a little wine on her hand and sucks it off, then for a second considers drinking what’s left in a glass, before relenting and washing it. A couple of movements, perhaps five seconds, and we understand potentially years of Sara’s life. It’s a piece of pure cinematic storytelling.

Little things unpack big stories throughout the film, thanks to the sensitive and artifice free performances. The relationship between Sara and her Dad has a naturally tense feeling to it, doubtless aided by the real life relationship between the actors, the history between the characters feels present in every moment. Outside of these scenes, the same unforced realism comes through in Greta Fernández’ performance. Whether Sara is at work, at home, or with her brother (another beautifully drawn relationship) there is never a sense of an actor playing a scene; the observational quality of Belén Funes’ direction coming through in performance as well as in camera. The victories may be small, but we feel them all the more powerfully for that, one sequence in which Sara learns she’s passed her probation at work is particularly good, capturing a warmth that we sense she feels too seldom as she’s trying to get by.

The film does build to a big narrative event, but even there Funes and co-writer Marçal Cebrian resist any urge to grandstand, landing on an ambiguous but deeply moving final image that underscores the tug that we have felt in Sara throughout. This is a notable debut from Belén Funes, a film that delivers but also promises many interesting things for the future. It points to director with a strong but unobtrusive eye and a great command over casting and performance. It’s a quietly excellent film, and one you should make time for at LFF.

★★★★

No comments:

Post a Comment