Dir: Ishiro Honda

Godzilla looks like, and has often been thought of, as a silly film about a giant dinosaur, spawned by radiation, destroying much of Japan. It is that film to some degree, and it’s possible to have a good deal of fun watching it that way, but there are other ways to look at Godzilla that give it rather more depth and place it in an interesting context among the world cinema of its time.

The film isn’t subtle about its anti-nuclear stance, and that makes it interesting in the larger context of 1950′s science-fiction, which, in the US, was driven by nuclear and cold war paranoia (look at their own films about giant mutated things, like the wonderful Them!) This is especially interesting coming from Japan, because, of course, they are the only country to have been attacked with nuclear weaponry, and were the first place to see the real devastation it caused. In Godzilla the monster is as much – metaphorically speaking – a walking H-Bomb as it is a giant mutated amphibious T-Rex. Now, the film comes across as quite silly as it tries to explain Godzilla (particularly when it dates dinosaurs to 2 million years ago, I mean, I know I shouldn’t be nitpicking, but that’s a 63 million year mistake), but, unlike the 1998 Roland Emmerich directed remake, it’s at least using its sometimes laughable explanations to say something. It’s not the most intelligent nuclear paranoia sci-fi, but Godzilla still feels interesting at a thematic level today, especially with the Fukushima disaster still relatively fresh in the memory.

At its heart though, for me, this was largely a fun monster movie. While most monster films now hold the main attraction back for at least an hour (often to justify a bloated running time), here director Ishiro Honda shows his hand just twenty minutes in, and that never stops Godzilla, in the next seventy minutes, from being a cool or a threatening presence. There is, now, a bit of a hokey feel to the special effects, which are sometimes quite obviously a guy in a suit stomping on miniatures. It doesn’t really matter though, the cheese factor is always high with a monster movie, and actually the monster itself looks good, and is well served by the black and white stock, which, for me, makes it feel more imposing (maybe because I just find it sillier when it’s a big green monster. The major set piece – the destruction of Tokyo – is very well realised, and makes much more sense then the remake’s New York rampages, mostly because here Godzilla doesn’t just vanish into thin air all of a sudden.

Godzilla holds up pretty well, almost sixty years on from its release. The script and performances are reasonably basic, but the deliver the story, the metaphor and the set pieces assuredly, but Ishiro Honda elevates the film with some stylish direction and impactful use of the monster. I’m not sure it’s quite the classic that some of the American sci-fi films of the 50′s are, but it’s an entertaining film that still has something to say today.

★★★★

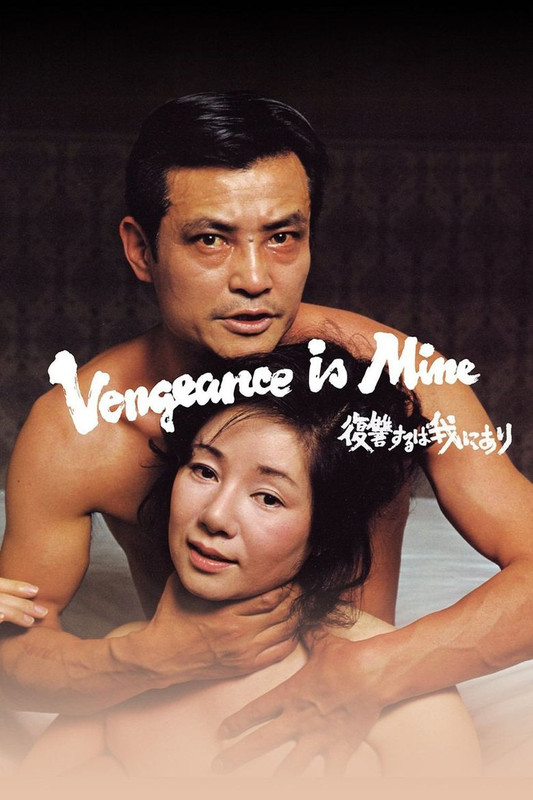

Dir: Shohei Imamura

I picked Vengeance is Mine as one of this month’s featured films because I really liked the first film I saw by director Shohei Imamura (The Insect Woman) and because I love vengeance films. Unless I missed something, this isn’t a vengeance film, however, it does share many of the traits I found so interesting in The Insect Woman, wrapping them up in a compelling narrative about an apparently motiveless serial killer, Iwao Enokizu (Ken Ogata) as Police interview him (almost completely off screen) about his 78 days on the run.

The film doesn’t senastionalise Enokizu’s life and crimes, rather it follows him quite dispassionately as he marries against his parents wishes, before leaving his wife (Mitsuko Baishô) with them when he’s imprisoned for the first time and then when he laves prison and fails to fit back in the film follows his murders and his escape to a guest house/brothel where the madam (Mayumi Ogawa) falls in love with him. In fact, the structure somewhat reminded me of The Insect Woman, in that Imamura is interested in more than the sensational, he digs into his protagonist’s life, and the lives around him, and like the earlier film Vengeance is Mine also has two pretty distinct halves, here largely defined by the dominant female presence in Enokizu’s life.

As much as the main storyline commands the attention, there is also great stuff around the edges, not least the creepy and intense attraction between Enokizu’s wife Kazuko and his Father Shizuko (Rentarô Mikuni), which threatens to come to a head while Enokizu is first in prison. This puts an extra, disturbing, dynamic into each of these relationships, and makes them just as gripping as the storyline about the murders.

Of course being that the film hardly deal with the killings themselves, especially in its long middle section, it relies on the actors to provide the tension, and they absolutely deliver. Ken Ogata is brilliant as Iwao Enokizu; communicating to us how unhinged and dangerous he is, while allowing us to see how he puts up a convincing mask of normalcy to the people around him. One great scene has him impersonating a lawyer, and despite knowing who he really is, you see why his marks buy into the fiction. Mitsuko Baisho and Mayumi Ogawa are both excellent as the women who – at least initially in Baisho’s case – love this charming killer. Wisely, neither they nor Imamura play on the danger they are in, and so what violence does occur is more shacking and scarier. What violence there is is pretty nasty. The film mirrors Zodiac somewhat in its structure, with two brutal and extended murder scenes happening right up front, and then the violence staying off screen for, in this case, almost the entire rest of the 140 minute running time. I’ve often seen violence in Japanese films rendered as outlandish splatter; high pressure hoses spraying blood from neck wounds etc, but Imamura does it differently; this violence is up close, extended, personal and difficult, and that’s why the film gets under your skin.

There are elements here of the later Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, which also puts a motiveless, patternless serial killer in his social context (though this film offers a resolution, where that one does not), and if slight overlength and occasional digressions from the thrust of the film keep Vengeance is Mine from being quite as good as Henry, it’s a close run thing and this film really makes me want to dig in to Imamura’s work at the first opportunity.

★★★★

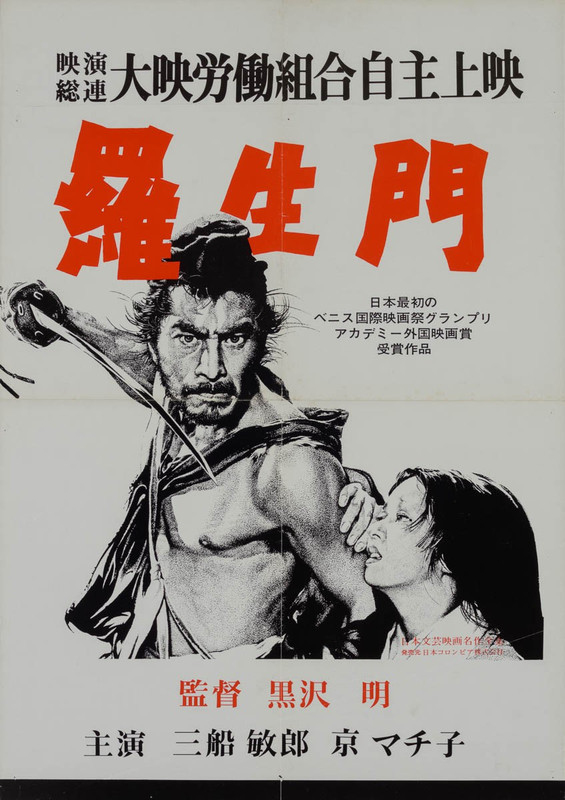

Dir: Akira Kurosawa

Confession time: I am a 31 year old who has the gall to call himself a film critic, and this was the first time I had ever seen an Akira Kurosawa film. I know. Shut up. Kurosawa is one of those filmmakers with a reputation and a filmography so big that it’s almost intimidating; do you start with a classic and risk disappointment? Do you start with something lesser known and build to the famous work? I decided to start with a notable film, and one that I knew something about going in because of its pervasive influence. How pervasive is that influence? Pervasive enough that anthropologist Karl G. Heider coined the term ‘Rashomon Effect’ to describe the effect of perception on the subjectivity of recollection. Or, to put it in simpler terms…

Rashomon unfolds the story of what looks to be the rape of a woman (Machiko Kyo) and the murder of her husband (Masayuki Mori) by a notorious bandit (Toshiro Mifune). The story is told from four perspectives, each related as testimony in court, first by the bandit Tajomaru, then by the wife, then by the spirit of her dead husband (speaking through a medium) and finally by a woodcutter who witnessed the events. We watch each version unfold as reconstruction.

The structure of Rashomon has been emulated many times (a notable recent example being Zhang Yimou’s Hero) and it is easy to see why. The way the film unfolds makes demands on us as an audience to think about each version of the story, and to decide which of the versions – if any – we find credible. The great strength of the film is that it is equally as easy to find yourself sucked into any version of the story,because there is never anything truly outlandish suggested, and the performances always remain consistent and strong throughout. It’s also possible to see each story as somewhere between lie and fantasy, because we only ever see the events as a story told after the fact, and because the forest clearing where Kurosawa stages most of the action feels almost like a self contained world, a little removed from the real (this also seems to be suggested by the slightly unnatural shimmering light).

Toshiro Mifune was often said to be Kurosawa’s alter-ego, I hope that’s not the case here, but he’s brilliant as the sometimes unhinged Tajomaru. The moral code the people in this film seem to live by is difficult to relate to (much conflict revolves around the fact that once the Woman has been raped somebody has to die, because she cannot stay married to her Samurai husband while there is another man alive that she has been with), but when these ideas are expressed by Tajomaru, who seems crazed at his trial and driven into something of a frenzy by the first appearance of Kyo’s character you see them as coming from a place that is driven not by an idea of honour but by his lust for the woman.

Machiko Kyo’s character is probably the one who changes most in each telling of the story. In all versions she is a victim, but what happnes after the rape varies greatly. In her own version the woman is further victimised by a husband who stares at her with contempt, but in others she is more manipulative, spurring on the fight between Tajomaru and her husband. Kyo is excellent, shading the character slightly differently in each version of the story; giving her strength in some and emphasising weakness in others. It’s the film’s most complex role, and she does it great justice. Masayuki Mori has rather less to do for much of the running time, given that he spends a lot of his screentime tied to a tree, but he’s very effective in what is a rather cold and unsympathetic role.

Rashomon is a complex film, and I’m sure there is much more to it than the relatively simple question of which is the true version of events. As an introduction to Kurosawa I felt it was ideal; it’s short and moves fast through its multi-levelled story, but never forgets to pause for breath or to give its few characters real colour. It looks beautiful, and is cut intelligently and relatively fast for its time, which injects both pace and variation into what could – given that it takes place largely on a single confined set – become a slightly stagy visual experience. I’ll certainly go back to this film in future, because I feel that, as great as I found it on a first watch, I’ve a lot more to get from it yet.

★★★★★

★★★★★

No comments:

Post a Comment