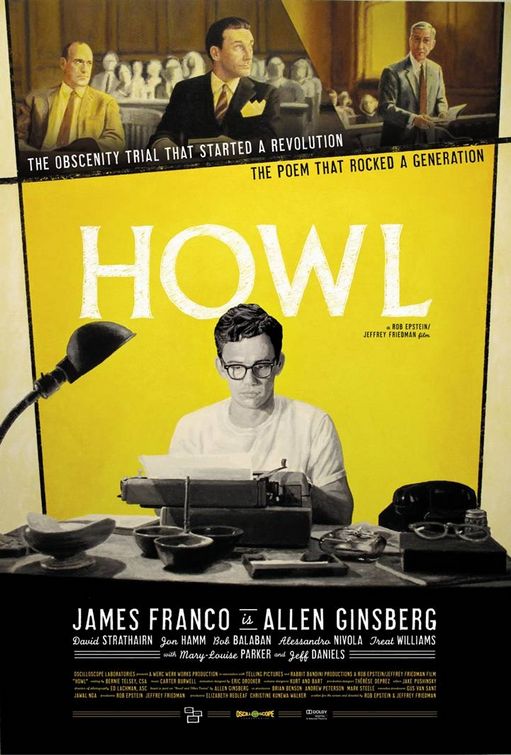

Howl

Dir: Robert Epsitein / Jeffrey Friedman

This biopic of Allen Ginsberg doesn’t, unlike most biographical films, attempt to tell the story of its subject’s whole life. Instead, the film adopts a very specific focus on Ginsberg’s most famous work; the titular, four part, poem Howl. It focuses on Ginsberg (James Franco) as he writes and performs Howl in 1955, and documents events in 1957, as Ginsberg is interviewed while Howl is being tried for obscenity. The dialogue is, apparently, entirely drawn from interviews and trial transcripts. Despite the fact that Howl is unusually specific in the time period it focuses on, the film can still feel rather scattershot at times, as if it is trying to explore this undoubtedly important piece of work from too many angles all at once.

The film largely falls into three parts, which are intercut throughout. The first is a (presumably complete) reading of Howl itself. This was probably my least favourite part of the film, not because Howl is obscene or offensive, more because I found it rather pretentious and self-indulgent. However, that’s mitigated by the way the reading is presented, in that it is rendered with some genuinely beautiful animation, which illustrates, in a slightly abstract manner, Ginsberg’s words. The second major part of the film is the obscenity trial, at which Ginsberg was not present, and it is here that the starry cast make their presence felt. Most of the roles are cameos, but everyone makes an impression, especially Mary Louise Parker, in an atypical role as a very prim high school English teacher and Jeff Daniels as a pompous poetry professor. The trial scenes are, however, dominated by the two attorneys, played by David Strathairn (prosecution) and Jon Hamm (defence). Good though the acting is here, there can’t help but be a slight stiffness to the sequence, shackled as it is to the transcript, and it becomes overtly preachy towards the end of the film.

The one thing you really can’t fault about Howl is James Franco’s performance, which dominates the film despite the interview sequences in which he’s on screen being relatively short. He reads Howl brilliantly, accentuating the percussive language, and completely disappears as Ginsberg. If the film as a whole doesn’t come up to the level of Franco’s performance (and it doesn’t) then it’s not for lack of effort. Howl throws a lot of things at the screen, not all of them stick, but it’s far more interesting than watching one more run of the mill biopic.

★★★

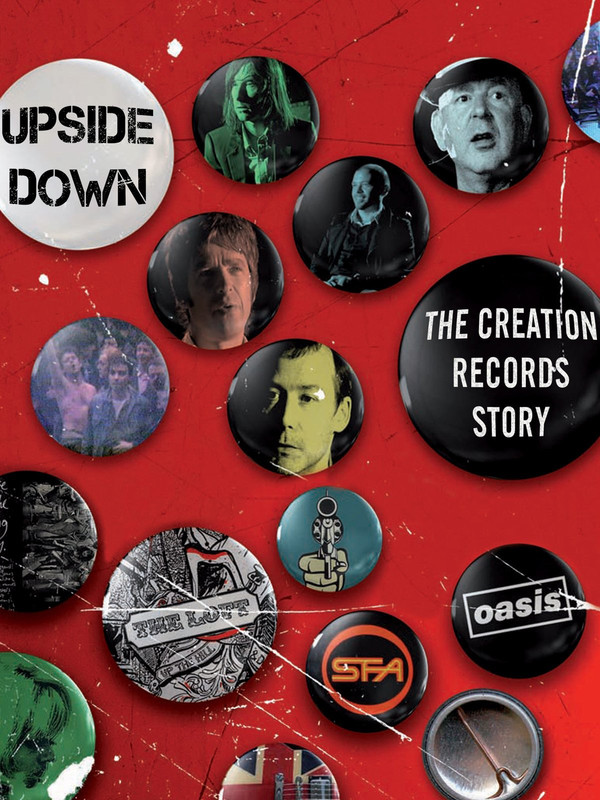

Upside Down: The Creation Records Story

Dir: Danny O'Connor

Creation Records, in many ways, defined what my teens sounded like. Oasis were so inescapable in the mid 1990’s that not only did Creation reap truly huge record sales, but every other label began to sign bands who sounded like they should have been on Creation (and, let’s be frank, were in many cases far better than Oasis). That period forms part of the story in Danny O’Connor’s hugely enjoyable documentary about Creation (and, to a large extent, its founder Alan McGee) but what the film is more interested in is the journey to that point.

We discover that that journey was mostly undertaken in haze of drugs and parties, that Creation was always just a half step from bankruptcy, and that it was run not so much by businessmen as by insanely devoted music fans who were simply desperate to help bands release albums and singles they loved.

The story is told in great detail, with warmth and humour, by the people who lived it, notably Alan McGee, co-founder Dick Green, Primal Scream’s Bobby Gillespie (a longtime friend of McGee’s, even before they were playing and releasing music), My Bloody Valentine’s Kevin Shields and Oasis’ unfailingly entertaining Noel Gallagher.

The Creation Records story could easily have been told on television, but director Danny O’Connor’s treatment, though it’s largely just talking heads and clips of bands, feels cinematic. That’s largely thanks to the beautiful black and white cinematography employed for the interviews and to the well designed and dynamic graphics. Archive footage of the bands is used intelligently throughout, adding context to the story rather than stopping it dead for musical interludes (though it has to be said, I’m still of the opinion that ANY use of The Boo Radleys Wake Up Boo, whatever the context and however brief, should be punishable in law).

Of course, music is the heart and soul of the film, and the love of it bleeds through almost every interview, especially McGee’s. The soundtrack is, obviously, stunning, showcasing bands I’d never heard of, bands I need to discover, bands I’d forgotten I liked… and Oasis. At 101 minutes, Upside Down does start to feel a little baggy towards the end, at which point it also seems to rush through the last few years, leading to a few potentially interesting avenues going unexplored (in a film so in thrall to the effects of drugs on music, why is there nothing about the making of Oasis’ coke hazed Be Here Now?).

For the most part though this is a fascinating story, well told, and packed to the gills with great music and well worth seeing for anyone with a passing interest in the indie music scene of the 80’s and 90’s. Beware though, seeing this film may mean that you’ll be spending obscene amounts on albums.

★★★

Blessed Events

Dir: Isabelle Stever

It’s not often, you may have noticed by now, that I’m lost for an opinion, but five days after seeing it, and having thought about it a lot, I still don’t know whether Blessed Events is a good film or not.

The film is about Simone (Annika Kuhl) a German woman in her mid thirties who becomes pregnant after a one night stand. When she tells the father to be (Stefan Rudolf) he’s very happy. They start a relationship, buy a house, and begin preparing for the baby. However, Simone doesn’t seem so excited, and as the pregnancy goes on she seems to grow ever more disenchanted with it.

Very little actually happens in Blessed Events, but what keeps it intriguing is the fact that the whole film has an atmosphere of tension and threat about it. It’s acutely felt in Annika Kuhl’s performance, despite the fact that she gives little away outwardly there is an ever present fear that Simone’s detachment is just a few seconds from making her do something terrible to herself and her unborn child. The problem is perhaps that the film explains nothing. Simone’s feelings about the pregnancy are never vocalized, her relationship with a mysterious bearded man who we assume to be an ex (Arno Frisch) is never addressed in any detail and for all the sense of impending horror nothing ever actually happens. As an exercise in extended tension, Blessed Events is interesting, but there’s no payoff.

The performances are strong, especially given the constraints of the often rather banal script, and I suspect that Annika Kuhl, though she doesn’t really have a lot to do here, is a fine actress, but it’s hard to judge when the atmosphere of the film feels so strange and surreal. Isabelle Stever maintains a chilly distance with her direction, and there are some striking visuals here, but there are also some inexplicably odd recurring choices. Why, for instance, are there so many shots in which characters heads are outside the frame? However, Stever does pull out one great moment, with an enigmatic final image, which will have anyone who sees this movie engaged in a raging debate about what happens in the minutes after the credits roll.

Blessed Events definitely isn’t uninteresting, but as to whether it’s any good? I’ll have to see it again and let you know.

★★★

Happy Few

Dir: Antony Cordier

It’s not that Happy Few is a bad film, I just feel like I’ve seen it before. This French film about two couples (Marina Fois and Roschdy Zem and Elodie Bouchez and Nicolas Duvachelle) who begin swapping partners on a ‘no rules’ basis just feels so familiar throughout, even down to the fact that it is very easy to see who among the group will be the first to raise a problem with the arrangement, and who will start developing some real feelings. Because of this familiarity and predictability, Happy Few feels pretty long. It’s notable in the film’s last twenty minutes or so, during which I expected the credits at the end of every scene.

The thing is though; this is not a badly made film. Antony Cordier and Julie Peyer’s screenplay establishes four very individual characters, gives them each a personality and has a few witty exchanges (one about sexual feng shui is notable). Cordier’s direction isn’t bad either; as even in the many, many sex scenes he finds a lot of variety in his shots.

Best are the performances, all of which are pretty solid. Zem and Bouchez are well matched; both darkly charismatic, but it is Nicolas Duvachelle and Marina Fois who walk away with the acting honours. Fois is especially good, visibly hiding real hurt beneath a façade of disinterest in what her husband and his lover do and real feelings for her lover beneath a detached pursuit of pleasure. The sex scenes are frequent and exposing (and in one case extremely convincing), and the cast deserve some recognition for their fearless performances.

I want to like Happy Few more, but at the end of the day, good as many of its parts are in and of themselves, the film as a whole is not the sum of them. It just never quite engages you in the drama as it should, largely because it’s always obvious where it is going.

★★★

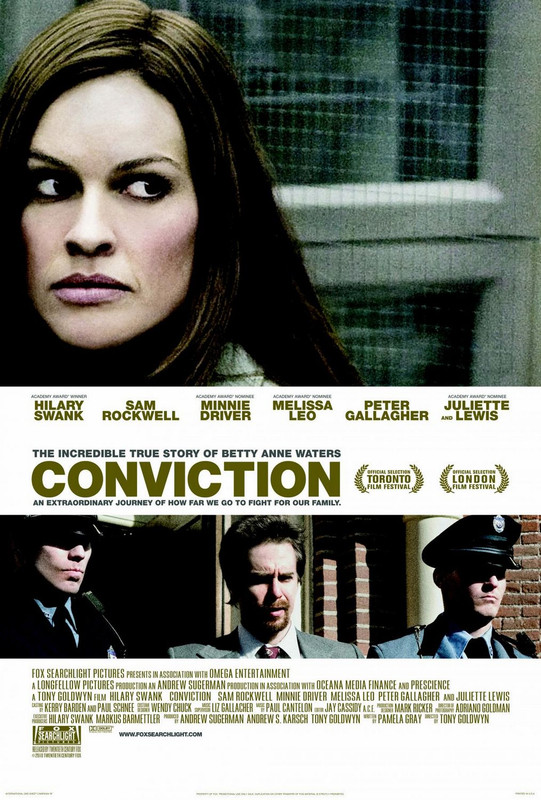

Conviction

Dir: Tony Goldwyn

The story of Betty Ann Waters (played here by Hilary ‘please can I have an Oscar?’ Swank) is amazing. Originally a high school dropout she got a degree and went to law school in her spare time over more than a decade, so that she could attempt to free her brother Kenny (Sam Rockwell) from a life without parole prison sentence for a crime she believed he didn’t commit. It’s an incredible story, and it deserves much more than this overgrown TV movie to tell it.

Conviction (the clanging double meaning of that title really tells you everything you need to know) isn’t ever bad, the problem is that it’s never good either. It’s like a Big Mac; sure it might be satisfying in the moment, but it’s got no nutritional value and it looks, smells and tastes like every other Big Mac you’ve ever had (and it comes with a slice of processed cheese).

The performances are all resolutely average. Hilary Swank acts her hardest as Betty Ann, but she’s never convincing in the slightest, the incredible actor who vanished into Teena Brandon’s skin in Boys Don't Cry appears to be gone and what we have here is a grandstanding 90 minute pitch to the academy, not once did I stop thinking ‘oh look, Hilary Swank sitting the bar exam; oh look, Hilary Swank cooking; oh look, Hilary Swank failing to look like she’s 22’ and variations on that theme. Sam Rockwell is a little better, but again there’s just that sense that you’re watching someone act the whole time, he’s usually such a subtle actor but here, from his accent on down, he’s often cartoonish. It’s nice to see Minnie Driver in a movie again, and she doesn’t seem to have aged at all, which is odd, but appealing as she is she doesn’t have a lot to do, or much of a character beyond ‘supportive friend’.

As a director, Tony Goldwyn doesn’t do anything particularly inventive. He presents the film in a straightforward, evenly lit, personality free way that any Hollywood hack could manage. Unfortunately there are a few areas where he drops the ball quite spectacularly. The biggest of them is the issue of the timeline. The film covers at least 20 years of Betty Ann Waters’ adulthood (it took her 18 to free Kenny) and in that time the sole concession to the passage of time on Hillary Swank’s face is the fact that in the scene in which she’s meant to be in her early 20’s she wears a lot of make up and has big hair. It’s a small issue, but a distracting one because, at a certain point, you begin to wonder where Betty Ann has hidden that picture of Dorian Gray. The age issue and lack of aging make up also results in some other (pretty hilarious) problems, notably Clea DuVall looking about five years older than her screen daughter Ari Graynor and the fact that Betty Ann’s teenage sons don’t age for about six years.

A few of the cameos work well, with Melissa Leo, Karen Young and Juliette Lewis all briefly enlivening this very middle of the road movie, but none of them having enough screen time to make much of an impression on Conviction’s utter, overwhelming averageness. You’ll have seen worse movies, but even in a bad week and certainly at a London Film Festival gala, you can do better.

★★

No comments:

Post a Comment