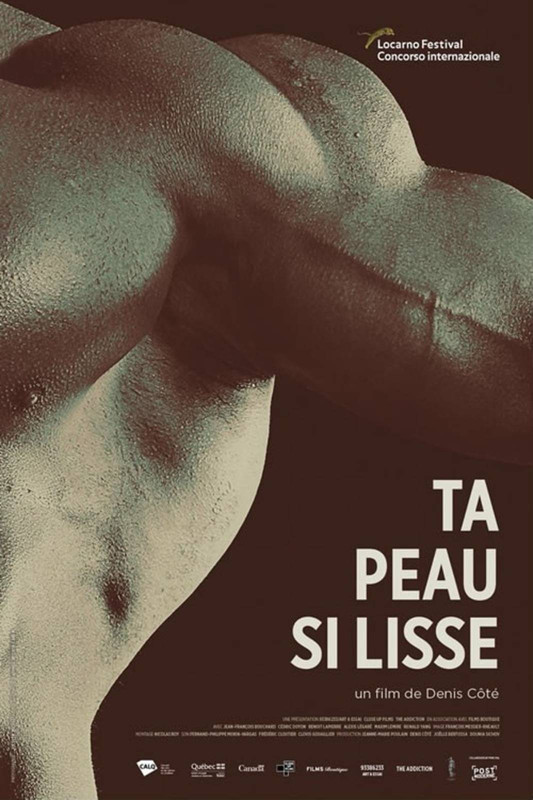

A Skin So Soft

Dir: Denis Côté

Denis Côté’s bodybuilding documentary has much more in common with Fred Wiseman’s reflective Boxing Gym than it does with the bravado and myth-making of Pumping Iron. Côté follows five French-Canadian bodybuilders, at various stages of their lives and their sport, as they go about their daily lives, training as well as doing other more mundane things.

Near wordless for much of its running time, the film instead finds insight into its subjects purely through observing them, fitting in a sport that is, whatever the route to get there, entirely about physicality. This can be mesmerising. The first twenty minutes of the film introduce the characters in almost total silence, following their morning routines. The youngest of the men trains, his Mother visible through the basement window, gardening above him as his weights clip their frame as he lifts. Another man eats breakfast while watching youtube. I couldn’t tell what he was watching, but from time to time he seems to choke back tears. These and other moments - Max, the wrestler, insisting to his wife that he’s “fine” despite the fact he’s hardly spoken to her in two days, for instance - linger in the memory for the amount of intrigue and insight they pack into images that we have to take purely on their own.

There are a few dialogues; the terse conversation I mentioned between Max and his wife stands out, as does the young bodybuilder telling his girlfriend he can’t be both her boyfriend and her trainer, especially if she’s not going to apply herself fully. Almost every other word spoken though is about training in some way, whether it’s the magnificently bearded Alex telling his masseur “I hate you” or the chatter between the guys when they all go for a weekend away.

Côté’s near total reliance on pure physicality does, however, have its downsides. Sometimes it feels as though he’s cutting around conversation. In the closing scenes on their weekend away, the bodybuilders are clearly friends, and talking amongst themselves. It would be good to see, and hear, more of that, to get more of an insight into the dynamic between them, and where the line lies between competition and friendship.

A Skin So Soft sometimes gets beneath the tough surfaces of the men it profiles, but it also often feels like it could go deeper. It’s an interesting film in its quietness but, for me, also sometimes limited by it.

★★★

★★★

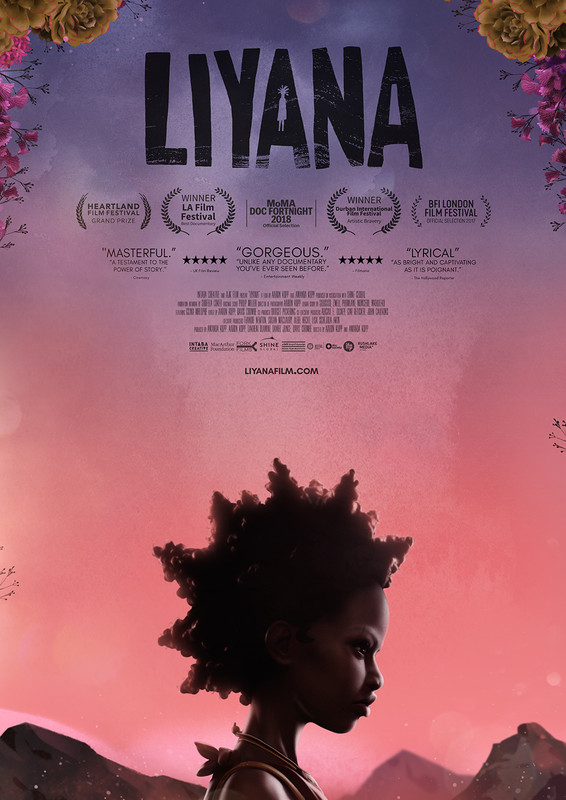

Liyana

Dir: Aaron Kopp, Amanda Kopp

Liyana is a story about storytelling, but it’s about a lot more than that too. The film follows a group of children in an orphanage in Sawziland who are asked in a workshop to collaborate, with children’s author Gcina Mhlophe and with each other, to create a character and a story. Their character is Liyana; a strong girl about their age, born into a family in which a drunk and abusive father contracts HIV and passes it to his wife, orphaning Liyana and her young twin brothers. One night, thieves come to Liyana’s home and kidnap her brothers so Liyana, taking one of the bulls the family keeps along with her, must set out to find them.

The story the children invent is interesting and entertaining in its own right. They set the odds against Liyana, but they give her plenty of agency, they make her brave and resilient and they create a narrative full of perilous set pieces for her to triumph over, with the help of the bull. We see the story unfold in beautiful animation by Shofela Coker, which makes Liyana unusually cinematic for a documentary.

What’s really compelling about Liyana though, and makes it remarkable, is watching the children create this story and understanding why they are writing it as they are. It is often said to young writers that to begin with you should write what you know. Tragic as it is, that is what these children are doing. It cannot be lost on us that a huge percentage of these children have been through much of what they put Liyana through. When deciding on the overall narrative there is discussion about what sets Liyana on her quest and it is clear that the idea of the thieves resonates, at least partly, through experience. This is even more true of the fact that Liyana finds herself orphaned by AIDS. A full 25% of Swaziland’s adult population has HIV or AIDS, and it is almost certain that many of the orphaned children writing Liyana’s story were orphaned for that reason.

The film industry and fan communities have recently been having a lot of conversations about representation. Liyana is the perfect example of why those conversations are important. These children don’t often get the chance to have their stories told cinematically, and when they are it is often through the filter of an industry that is almost entirely white at the top. Here they are able to control their own narrative. They seems to grab that power with both hands, giving it to Liyana and thus back to themselves. It becomes clear in interviews late in the film just what this ability to represent themselves means to these children. “When Liyana’s story keep going, mine will keep going” says one. That’s what’s important here, these children are empowered by storytelling, allowed to write a happy ending for Liyana and thus for themselves. I hope they all get the ending they write.

Liyana is a great example of why the Family strand of the London Film Festival should be covered more, it’s just the kind of film we should be encouraging children to see (I’d suggest it for ages 10 and up, thanks to a few tough themes). Hopefully it will encourage them to tell their own stories, now and in the future.

★★★★

No comments:

Post a Comment