I just answered a question on Twitter asking what our favourite films so far this year had been and in answering it I realised that I had not yet run my reviews, originally written for the now defunct Verite magazine, of two of my choices for that list, which seems important given that the questioner had only heard of one of my selections. Thanks, as ever, to Verite for letting me repost these pieces.

There are spoilers in the review of The New Girlfriend.

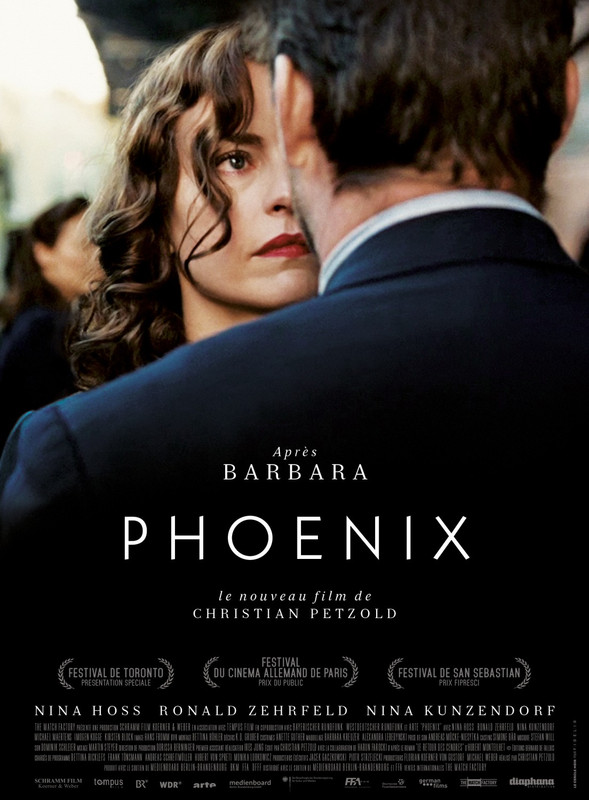

Phoenix

Dir: Christian Petzold

Director Christian Petzold has often drawn on other films for inspiration. Hitchcock has long felt like a key influence on Petzold, bleeding into Jerichow, Barbara, and early TV effort Something to Remind Me, but never has Petzold drawn so heavily on Hitchcock as he does in Phoenix, which is steeped in the influence of Vertigo.

Petzold's muse Nina Hoss (in her eighth collaboration with the director), plays Nelly, a Jewish woman who has survived the concentration camps but, when we meet her, has sustained severe facial injuries. She asks the reconstructive surgeon to make her look exactly as she did before. Nelly then returns to Berlin, looking for her husband Johnny (Ronald Zehrfeld). Nelly's friend Lene (Nina Kunzendorf) claims that Johnny was the one who betrayed Nelly, but she wants to discover if her husband still loves her. When Nelly and Johnny meet again he is struck by the resemblance but appears not know that she is his wife. Instead, he exploits that resemblance, getting her to 'impersonate' Nelly.

There is something disturbing in this story that goes beyond even Vertigo's obsessiveness. James Stewart's Scottie is trying to remodel Kim Novak into someone different, someone she never was. Not so the case here. Whether or not he's aware of it, Johnny is trying to make Nelly become his wife once more, but to his own exacting standards. It's a goal that can't, in either case, ever be achieved, but the impossibility of such perversity is magnified for paradoxically already having been achieved.

This is a film centered on Nina Hoss, specifically on her face. That should be enough to make you want to see it, because Hoss, beyond her obvious talent, has one of the most distinctive and fascinating faces in cinema right now. This is especially interesting in the context of Phoenix, because that very distinctiveness makes it hard to believe that Johnny could fail to recognise his wife. That interesting/frustrating ambiguity lingers for never seeing the full extent of Nelly's facial wounds (only a soldier wincing at them), and all we know of her before her disfigurement is the picture her surgeon is working from that shows Nelly laughing; not something Hoss gets to do much, here or in other films.

Also worth noting about Nina Hoss' face is the depths of its expressiveness and how its surface can shift like quicksilver. Playing two halves of a splintered psyche simultaneously, with only a glance she alternates between a sure-of-herself Nelly, wanting things to return to the way they were (evident early on in that request to the surgeon) and an uncertain Nelly, trying to figure if her husband did, in fact, betray her, and what he thinks of her now they're reunited. She's also Johnny's doll, playing dress up 'Nelly', trying to become the image he has of his wife in the flesh.

Hoss dons the different personas and confused states of minds like masks her character wears uncomfortably; from the bandages of the first fifteen minutes (more than a little reminiscent of Eyes Without a Face) to how the recently reconstructed Nelly now sees herself, and finally, Johnny's idealised version of the wife he recalls—the one that will make their old friends believe she's the 'real' Nelly. It's a performance that, were it in English, would sweep all the accolades come awards season. Hoss shows us the tangled confusion of Nelly's mind with subtle shifts in emotional temperature that are tiny but telling.

Phoenix is an exceptionally strong film and Petzold's direction matches the lead performance. Characteristically, he plays off his influences without allowing the film to become Hitchcock karaoke, and giving 1945 Berlin historical verisimilitude, he uses the camera to be just as true to the emotions of the characters, capturing every moment of exposing vulnerability that Hoss and Zehrfeld contribute to loaded silences, lending their highly dysfunctional relationship an interior richness. Yet all this subtly and intrigue pales next to the mastery of the final scene. Without giving too much away, Nelly's heartrending performance of 'Speak Low', is built off just a few images and a devastating piece of silent acting from Zehrfeld. With this, Petzold draws the themes and all the film's questions together in an astonishing whisper that goes off like a bang. Where Petzold goes from here will no doubt be interesting, but he's given himself a hell of a mountain to climb in having to follow such a powerful ending.

★★★★★

The New Girlfriend

Francois Ozon has brought a new film to the London Film Festival three years running, but 2013's Jeune Et Jolie suggested that a rate of at least one film a year was starting to take a toll on his work - much of which is soufflé light and fancy free, but even for him, Ozon's last was a shallow film crying out for more depth.

Thankfully, it seems Jeune Et Jolie was just a blip, as The New Girlfriend, adapted from a Ruth Rendell story of the same name, finds Ozon back on form, blending his mischievous side with a substantial (but hardly realistic) story, full of secrets that are practically impossible not to reveal when talking about the film.

The totally spoiler-free version of the review reads like this. A playful addendum to Ozon's grief trilogy (Under The Sand, Time To Leave and Le Refuge), The New Girlfriend finds husband David (Romain Duris) and best friend Claire (Anais Demoustier) dealing with the death of Laura (Isild Le Besco) in different ways. These coping mechanisms are predicated upon Ozon's chief preoccupation of sexual malleability and confusion. For his fans, The New Girlfriend is full of auteurist traits in the use of colour and offbeat humour, perfectly handled by an outstanding cast.

Discussing the film in any greater detail requires the revelation of a key twist, so stop reading if you want to go in cold, which is my recommendation.

Fifteen minutes in, we discover that David is, in fact, the title character. After his wife's death, he falls back into an old enjoyment of dressing as a woman, becoming closer with Claire as Virginia, a relationship she keeps from her loving but uncomprehending husband Gilles (Raphael Personnaz). Virginia is a persona who grows into a fully realised third main character, with Romain Duris physically, verbally and emotionally defining the split between the two personalities he's playing very capably. Ozon mines much comedy from his star's gender-bending, but its intent and effect are never cruel. The joke is often at David's expense, but Ozon never has us laugh at anything David himself would be upset by. Take for instance an early moment when David is having tea with Claire and his mother in law (Aurore Clement) in his own clothes. Gesturing as if to rub away some lipstick, he forgets he's not dressed as Virginia. Coupled with Demoustier's reaction it's one of many slyly funny, non-verbal embarrassments.

With the less showy role, Anais Demoustier has a grounding effect on the film, lending Claire a straightforwardness that gives us a way in to the characters and the story whenever Duris' dual performance might push the camp factor a little too far out for some. Claire seems a simple character, but her complexities lie under the surface and Demoustier lets them show through slowly. Virginia's observation that her friend often dresses in a masculine fashion is quickly followed by a sex scene in which Claire enacts a masculine cliché; rolling off her husband as soon as she's achieved orgasm and casually asking “did you come?” “No”, he says, “but that's okay.” The gender issues seeded in this scene pay off in a later sex scene between Claire and Virginia/David. Demoustier quietly and heartrendingly articulates Claire's sudden kinship with Virginia. Despite never having been close to David, she like him, is trying to fill the void Laura has left in their lives.

Laura is glimpsed only briefly (mostly in an opening flashback charting her friendship with Claire that feels like Ozon's take on the opening of Up), and while Isild LeBesco doesn't have time to give us a rounded character, her radiant presence is more than enough to suggest how much darker the lives of these characters are without Laura in them.

In changing some of its fundamentals, re-calibrating its tone and adding a great deal to Ruth Rendell's ten-page story (including a completely different ending which closes the film out with the most auteurist image of Ozon's career), there's a feeling of a filmmaker at play, despite the grief which subsumes the players. Claude Chabrol's La Ceremonie is more along the lines of what might be expected from a straight Rendell adaptation, but with a distinct lack of foreboding or impending violence, Ozon brings a lightness of touch to even the most dramatic of scenes, enabling him to seamlessly shift from frolicsome scenes such as Claire and Virginia's first outing together and moments suffused with a crippling sense of grief, such as David dressing his wife's body for her funeral. Between these contrasting registers, Ozon's customarily unblinking depiction of sexuality against the hetero-normative grain is evident throughout, with one sex scene in particular, the strangest, most emotionally fraught and complex he's ever directed. Like the sexuality, the film's structure is fluidly subversive. The sequence of Laura being dressed for her funeral is echoed at the end, its second occurrence making poignant use of a song that Virginia and Claire hear a drag act sing at the film's midpoint, movingly literalising its meaning.

For years, Francois Ozon's films fell into two categories; the playful and the severe. Recently, with In the House and now The New Girlfriend, it's fascinating watching him begin to draw those two sides off his personality as a filmmaker together. The mix is less successful here than it was previously, largely because Claire's husband is rather underdeveloped and one note and the existence of Laura's daughter Lucie is almost entirely forgotten for an hour of the run time. Still, The New Girlfriend is a great film, often moving and amusing in the same moment and boasting two subtly soulful lead performances.

Much more than a return to form, it's a superb reaffirmation of Ozon's status as one of the best directors in world cinema, ranking in the top tier of his own rhapsodically tender and strikingly imaginative filmography.

★★★★★

★★★★★

No comments:

Post a Comment