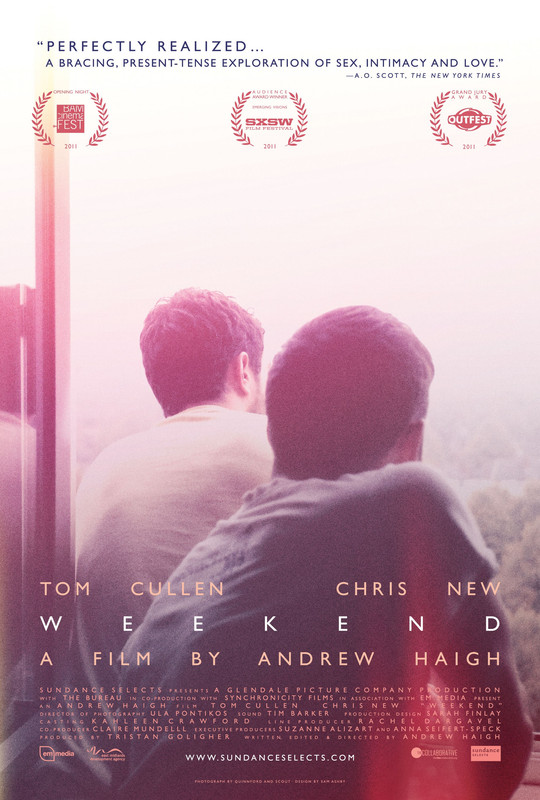

Weekend

Dir: Andrew Haigh

I've been hearing great things about Weekend, from just about all quarters, since last year's London Film Festival, but despite many opportunities, and not by design, I just kept managing to miss it, so where better to rectify that than at LLGFF?

At the Q and A after the film I heard director Andrew Haigh say that he wasn't keen on the many reviews using the word 'universal' to describe the film, as he felt that was a tactic to give straight audiences 'permission' to see the film, which we shouldn't need to do. I agree with the second part. At the risk of upsetting Haigh though, 'universal' was exactly the word that ran through my head, and not because this is a 'gay' film. The specifics of the relationship depicted here aren't something I have experience of, not merely because it's a gay relationship and I'm straight, but because I also happen not to have met someone for a weekend, fallen for them, but had to say goodbye almost as soon as I've met them. What does speak to me, and what will speak to almost any audience member, is the feeling of this film. Who hasn't found someone they think they might love and then lost them? Maybe neither of those things happened with the speed depicted here, maybe they did, but we've all felt like this, and that's why Weekend feels universal.

What is outstanding about Weekend is how emotionally articulate it is. This is largely down to the combination of Haigh's intelligently observed screenplay and tremendously naturalistic performances from leads Tom Cullen and Chris New. Cullen plays Russell, a gay man out to his friends, but not terribly comfortable being out in the wider public. At a gay bar he picks up Glen (New), and what seems likely to be a one night stand ends up developing quickly, even after Glen says that at the end of the weekend he's going to art college in America. Russell and Glen aren't the sort of shells we're now conditioned to accept as characters by most movies; they feel real and rounded, and for everything we do learn about them Cullen and New hint at much more going on beneath the surface. The conversational scenes between the two, particularly a drug aided discussion of marriage, have the loose feel of two people just talking the day or the night away, and that's the feeling of the whole film; it doesn't seem acted but like a little glimpse into 72 hours in the lives of these two people.

Neither Russell nor Glen is perfect, and even in the short time they spend together you can see the things that make them different and why a relationship would be hard, but they are both sympathetic, both people who feel real and who you can identify with, and that makes the relationship one you root for, even if you're reasonably sure how things will end up. To his credit, Haigh employs and plays with cliche beautifully with the film's ending, crafting something that feels both classic and a little different. Nobody needs permission to watch or enjoy Weekend, but if you have yet to, consider this a little friendly encouragement.

★★★★

The Mountain

Dir: Ole Giæver

The Mountain of the title is, obviously, one big snowy metaphor. As the film opens we find Nora (Marte Magnusdotter Solem) and Solveig (Ellen Dorrit Petersen) climbing, a long term couple, they are clearly miles apart at the moment, and the film slowly lets us in on why that is and why, with Solveig three months pregnant, she is insisting that Nora join her in this trek.

As the information begins to leak out we can probably put together the story before the film tells it, but then this isn't really about what happened the last time Nora and Solveig were on the mountain, it's about the aftermath, what it has done to each of them and to their relationship. With only two characters in the film, The Mountain hinges entirely on the strength of its performances, and fortunately Solem and Petersen prove more than equal to the challenge of the emotional heavy lifting they each have to do.

The film really passes no comment on the fact that the couple at its centre are both women, it just happens to be so, and the story would be (largely) the same were they a heterosexual couple or two men. That said, the fact that both the main characters are women does give an important extra physical and emotional gravity to what has happened, and tensions between the birth and non-birth mother of the same child is a dynamic I've never seen on screen before. The performances get better and better as the emotions become more and more fraught, and the film is only really let down by an ending that feels a shade against the prevailing tone of the film as a whole. Until those last couple of minutes this is a refreshingly adult drama that deals with a difficult subject articulately.

★★★

This is What Love in Action Looks Like

Dir: Morgan Jon Fox

Documentaries often tell stories that are harder to believe than fictional films. Even in spite of knowing about it long before I saw this film, I still find myself incredulous at the idea that some parents' reaction when their child comes out to the is to send them, against their will, somewhere like the Refuge camp run by the more than slightly ironically named Love in Action, where they can, potentially, be 'treated' for and 'cured' of their homosexuality.

In 2005, a teenager named Zach Stark was told by his parents that he would be going to one of these camps, he then blogged about it on MySpace (this being 2005), posting the list of rules that Love in Action expected him to obey while he was there. From there the post was picked up, and a small group decided to protest at Love in Action every day that Zach was in there (the film is named for the text on one of the protestors banners), eventually the story was picked up national and international media, and began to make waves.

Director Morgan Jon Fox and his team have spent six years securing an impressive range of voices, from Zach and other people who went to Love in Action, some forced, others of their own volition as well as from the protestors and the former head of the Love in Action ministry. The views are perhaps, ultimately, slightly less diverse than I'd like - it would be good, for instance, to have someone in the film who felt that Love in Action's therapy had worked for them, though perhaps that absence speaks for itself. However, the varying perspectives from both within and without this organisation are always fascinating and sometimes shocking.

This is What Love in Action Looks Like is, or hopefully will be, an inspirational film, because as much as it's about Love in Action, it's also a film about how a small group of people really can make an important change in the world, not by violent means but by simply (and cleverly) saying: 'this is bad, and this is why'. Some technical aspects of the film are flawed (media clips are shown small, and on a background designed to look like the internet in 2005, and the emotive score sometimes overplays its hand when the image alone is plenty powerful enough), but these minor issues are easily overcome by the importance and the interest of this story.

★★★★

No comments:

Post a Comment