Dir: Quentin Tarantino

I was in my teens in the mid to late 90s, so of course I grew up a Tarantino fan. I remember the frustration of the long wait for Reservoir Dogs, and then Natural Born Killers to be released here; the first held up by BBFC, the second having its release cancelled by Warner Brothers after an 18 certificate was granted. I remember the shock of seeing Pulp Fiction at fourteen, rewinding it and rewatching it immediately.

My first Tarantino in the cinema was a bit of a disappointment at the time. Subsequently, Jackie Brown is clearly his greatest film. I bought into the mythology of the cool director who honed his craft not at film school but by watching videos and I revelled in much of the renaissance in independent cinema that his work seemed to usher in. I feel that Tarantino’s career, with Pulp Fiction as something of an outlier, can largely be divided into two eras: the genre pastiches and the alternate histories. Dogs was his heist film, Jackie his Blaxploitation movie, Kill Bill his kung fu picture, Death Proof a Roger Corman cars n' girls movie. Those elements that come from being steeped in genre lore recur in his war film Inglourious Basterds and his Westerns Django Unchained and The Hateful Eight— but these films are at least as concerned with remixing history as they are remixing genre, an aspect of Tarantino’s work I’ve never entirely warmed to, until Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood.

My first Tarantino in the cinema was a bit of a disappointment at the time. Subsequently, Jackie Brown is clearly his greatest film. I bought into the mythology of the cool director who honed his craft not at film school but by watching videos and I revelled in much of the renaissance in independent cinema that his work seemed to usher in. I feel that Tarantino’s career, with Pulp Fiction as something of an outlier, can largely be divided into two eras: the genre pastiches and the alternate histories. Dogs was his heist film, Jackie his Blaxploitation movie, Kill Bill his kung fu picture, Death Proof a Roger Corman cars n' girls movie. Those elements that come from being steeped in genre lore recur in his war film Inglourious Basterds and his Westerns Django Unchained and The Hateful Eight— but these films are at least as concerned with remixing history as they are remixing genre, an aspect of Tarantino’s work I’ve never entirely warmed to, until Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood.

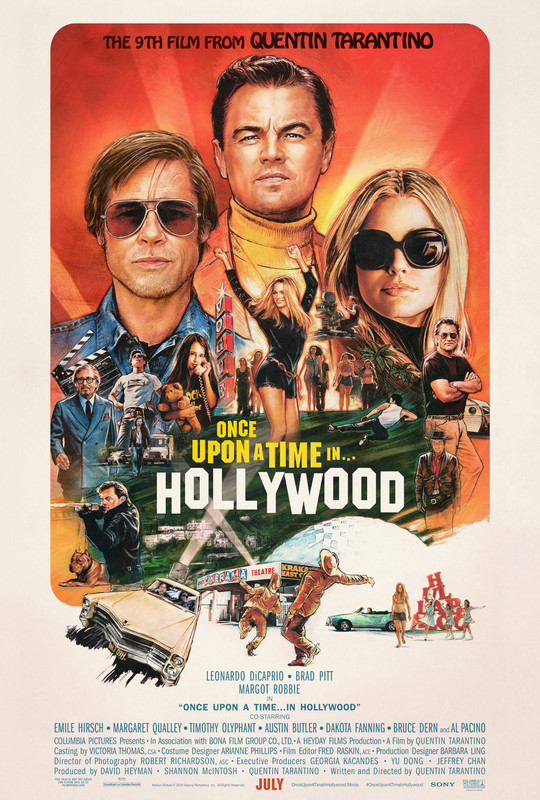

I first heard about this as Tarantino’s film about the Manson Family murders, but in truth it’s a shaggy dog story woven around 1969 in Hollywood, tangentially and intriguingly dealing with those events. Leonardo DiCaprio and Brad Pitt star as Rick Dalton, a washed up movie star, now flailing in TV and Cliff Booth, his stunt double/dogsbody. Rick’s disappointment in the direction his career has taken is accentuated by the fact that while he’s doing a guest part on a Western pilot, he’s living next door to Roman Polanski and Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie). Meanwhile, Cliff encounters one of the Manson girls (Margaret Qualley) and gives her a lift back to Spahn ranch where he and Rick used to work, meeting the rest of the Family in the process.

That’s only the barest bones of a film that, in its 162 minutes, encapsulates so much; from encounters with Bruce Lee (Mike Moh) and Steve McQueen (Damian Lewis); to cameos from the extended Tarantino family (Zoe Bell, Kurt Russell, Michael Madsen) and what is sure to be one of the year’s most controversial and difficult to address endings.

In some ways the film is guilty of all the typical excesses of its director’s oeuvre but it’s also his most reflective work; at times almost wistful, even in the midst of its most extreme moments.

In some ways the film is guilty of all the typical excesses of its director’s oeuvre but it’s also his most reflective work; at times almost wistful, even in the midst of its most extreme moments.

For the bulk of its running time Once Upon A Time… in Hollywood (a title whose significance is only fully clear when the card comes up at the end of the film) is a hangout movie, involving us in the minutiae of a couple of days in Rick and Cliff’s lives. There is some sense that what began as a working relationship has subconciously shifted to become a friendship of convenience. Still, we get a sense of the two as real friends despite the disparity of their Tinseltown status. Together or separately, DiCaprio and Pitt have seldom, if ever, been better than they are here. Pitt, now more than ever aging into a doppelganger of a 45-ish Robert Redford, gives Cliff a slightly melancholy sense of a guy who has just followed where his life has led him, ending up a little battered and somewhere in the forgotten middle of society orbiting the rich, famous and his formerly idolised benefactor. Earlier in his life, you might imagine Cliff getting pulled in when he meets Pussycat (Qualley), but the years we can see and feel in Pitt’s performance have given him a fine-tuned bullshit detector which works to ramp up the tension in the scenes at Spahn ranch. As with the scenes of him being both a gofer and a shoulder for Rick, Cliff is shown to be a caring person in the sequence at Spahn ranch, the tension driven by his sense that something is off, making him insist that he check in on the elderly George Spahn (a cameoing Bruce Dern).

It is in two closely related scenes centering on Cliff, that Tarantino hits the movie's only extended discordant note. During a lengthy flashback explaining why he’s no longer working as a stuntman, Bruce Lee goads Cliff into a confrontation on the set of The Green Hornet. This is a film that otherwise fantasises about redressing the balance on terrible events, but this image of Cliff—at least 40 in this scene—isn't just holding his own against an in-his-prime Lee, but at one point besting him. This isn’t just ludicrous, it leaves a bad taste in the mouth, especially when combined with a flashback within the flashback that winkingly suggests Cliff killed his wife. It’s a testament both to how inessential they are and how good the rest of the film is, that these scenes can largely be brushed aside, although they do leave the same lingering questions that have always clouded Tarantino's racial and sexual politics.

The Spahn Ranch sequence and the ending aside, Cliff’s story is about as loose and relaxed as he is. Rick's story by contrast is tense and internalised; from the opening realisation that the producer he’s talking to (Al Pacino, typically overblown) is telling him the sad truth about his fading career; to the scenes on the set of the pilot he’s shooting, DiCaprio conveys the sense of a man simmering in a crisis continually rising to the surface. By far the most interesting character moments occur on the set of Lancer. Tarantino indulges in extended screen time for these probing scenes of a formerly confident ego wracked with self-doubt. Particularly interesting is the scene in which a highly practiced Rick still manages to forget his lines while the cameras roll. When he’s on solid ground he’s good, playing the villain with relish but also real menace, but once he loses focus he becomes hammily overblown, voraciously chewing on lines now given as prompts, spitting them out with a disdain for himself that extends to a pitifully brutal, drunken self-critique in his trailer between scenes.

It’s a special kind of challenge to deliver a great performance through bad acting, but the subtlety of Diaprio’s work pays dividends, giving colour and pathos to Rick’s process and his character. As Rick unexpectedly finds himself talking to a child actor before a crucial scene, the Lancer set provides an equally unexpected glimpse of something more emotionally raw than anything Tarantino has previously written. Asked about the cowboy novel he’s reading, Rick instantly recognises parallels to his own fading career and breaking down. This and the instant shame this recognition arouses, causes him to somewhat cruelly lash out at his preternaturally gifted co-star. These are rich but subtle moments that contribute to this being career best work from DiCaprio.

It’s a special kind of challenge to deliver a great performance through bad acting, but the subtlety of Diaprio’s work pays dividends, giving colour and pathos to Rick’s process and his character. As Rick unexpectedly finds himself talking to a child actor before a crucial scene, the Lancer set provides an equally unexpected glimpse of something more emotionally raw than anything Tarantino has previously written. Asked about the cowboy novel he’s reading, Rick instantly recognises parallels to his own fading career and breaking down. This and the instant shame this recognition arouses, causes him to somewhat cruelly lash out at his preternaturally gifted co-star. These are rich but subtle moments that contribute to this being career best work from DiCaprio.

The most talked about aspect of OUATIH is undoubtedly the character of Sharon Tate and how she and the Manson murders tie into the narrative. It is at once very much a side story and the beating heart of the film. Tarantino has always been defined by his love of cinema, but he’s never romanticised it quite the way he does when Margot Robbie’s Tate goes to watch a public showing of The Wrecking Crew, in which she has a supporting role. We see her—bare feet up on the seat in front of her—enjoying the film but taking special pleasure in hearing laughter when her character “the klutz” gets a big reaction from a sparse audience, unknowingly watching along with the film's nascent star. This is a sequence about the magic of cinema and tragically snuffed out possibility. Splicing footage of the real Sharon Tate into this New Hollywood fairytale, Tarantino accentuates the artifice of his universe. Attention is drawn to the fact that Robbie looks little like the real life performer she’s playing, yet between them, actress and director make the connection between the avatar watching the film and the woman up on screen both believable and moving. We can see a process many actors must go through but which we’re seldom privy to. Watching herself up on the big screen, the movie’s Sharon seems to know that the audience's reaction and her rising star adjacent to the meteroic ascent of her husband, has opened up myriad possibilities, bathed in the warm glow of the projector.

Robbie, one of the best actresses to emerge as a star in the past decade, is truly wonderful as Tate. Though much has been made of her lack of dialogue, her luminous presence is felt throughout even when she's off-screen, floating through the film as a prematurely ghostly figure. Tate and Polanski are positioned as the Joneses Rick can no longer keep up with, but their idyllic bubble is soon to burst—though Tarantino clearly wishes that hadn’t been the case.

Robbie, one of the best actresses to emerge as a star in the past decade, is truly wonderful as Tate. Though much has been made of her lack of dialogue, her luminous presence is felt throughout even when she's off-screen, floating through the film as a prematurely ghostly figure. Tate and Polanski are positioned as the Joneses Rick can no longer keep up with, but their idyllic bubble is soon to burst—though Tarantino clearly wishes that hadn’t been the case.

I’m unconvinced by the controversy around what Tarantino elects to leave out about Manson and his beliefs; the cult leader exists entirely on the periphery. Similarly, the controversy about the violence of the final sequence feels overblown, even in the context of Tarantino's filmography. OUATIH revels in violence and yes, much of it is meted out against women, but it matters exactly who these women (and the men leading them) are and what they have set out to do. For Tarantino, and in the wider historical context, this deranged bloodshed is a means of enacting righteous and furious vengeance. In the world of the film, these unfathomable events will almost certainly be a story for only a day. Cliff and Rick’s actions create an alternate path for history, meaning what they do has none of the ramifications it does in the real world. It's interesting to consider how the sequence plays if the viewer knows absolutely nothing about the historical reality, but if they do, the reward is Tarantino’s most radically complex rewriting of history yet.

I’m unconvinced by the controversy around what Tarantino elects to leave out about Manson and his beliefs; the cult leader exists entirely on the periphery. Similarly, the controversy about the violence of the final sequence feels overblown, even in the context of Tarantino's filmography. OUATIH revels in violence and yes, much of it is meted out against women, but it matters exactly who these women (and the men leading them) are and what they have set out to do. For Tarantino, and in the wider historical context, this deranged bloodshed is a means of enacting righteous and furious vengeance. In the world of the film, these unfathomable events will almost certainly be a story for only a day. Cliff and Rick’s actions create an alternate path for history, meaning what they do has none of the ramifications it does in the real world. It's interesting to consider how the sequence plays if the viewer knows absolutely nothing about the historical reality, but if they do, the reward is Tarantino’s most radically complex rewriting of history yet.

As with all Tarantiono's post Jackie Brown output, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood's longueurs can go a little too long, though in this instance mostly by design and only occasionally. The gear shifts here would be easy to botch, but from its warm nostalgia to its violent excess and tense horror-inflected sequences pushed up against a surprising abundance of broad comedy, Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood mixes tones freely and with great success. The performances are uniformly excellent, not only the incredible leads, but many of the supporting playes, from a staked cast standouts include Margaret Qualley as the quintessential hippie chick, given an edge of danger by her associations, and a genuinely scary Dakota Fanning as Manson girl Squeaky. The film is also littered with one scene wonders like Julia Butters as Rick’s young co-star and Mikey Madison as deranged Manson girl Sadie. Robert Richardson’s cinematography beautifully captures a sense of period without feeling like pastiche, and he and Tarantino bring an especially beautiful eye to the TV pilot, making Lancer look so much more than the Western programme filler it's likely intended as. Overall, OUATIH is the richest, most mature and interesting film Quentin Tarantino has crafted in two decades. If the filmmaker remains true to his word and his next production is his last we can only hope he'll deliver at the same level and end his career on a suitably elegiac note, as he does with this film.

★★★★½

No comments:

Post a Comment