Dir: Celine Sciamma

Since 2008, writer/director Celine Sciamma has made her name exclusively in coming of age cinema, with her own films Water Lilies, Tomboy and Girlhood and the screenplays for My Life as a Courgette and Being 17, all five of them among the genre’s best in the past few years. As her first venture outside that genre, Portrait of a Lady on Fire represents a big change, but Sciamma’s cinema, while evolving, as it has with each work, still feels as raw and personal as ever with this move into period romance.

In 18th century France, painter Marianne (Noémie Merlant) is commissioned to paint a wedding portrait of Héloïse (Adèle Haenel). Because she doesn’t want the marriage, Héloïse is trying to avoid the painting, so Marianne must observe her during daily walks and work in secret. As the wedding grows closer, so do Marianne and Héloïse.

Described by Sciamma as a film about the memory of love, the jumping off point is the titular portrait. When Marianne is asked about it in a drawing class where she is both teacher and model we move straight into flashback, finding her arriving on the beach, above which sits the stately home where Héloïse lives with her mother (Valeria Golino) and their young maid Sophie (Luàna Bajrami).

Like many love stories, Portrait of a Lady on Fire is initially a slow burn. In her aim to film the growth of desire, Sciamma uses both this slow pacing and the composition and timing of her images brilliantly. The film is incredibly sensual and tactile, taking in details of form and texture in a way that seems to try to replicate Marianne’s painter’s eye for detail. This is seen in how the camera dwells on things like the folds of a dress, as well as in the way it regards Haenel, taking in every angle and line, allowing her to give a performance that works in tiny nuances, especially during the first half of the film, which is essentially a process of breaking through Héloïse’s shell. The first time Haenel smiles in the film, which is almost imperceptible and almost halfway through, is the first moment that begins to trigger the realisation of the desire and slowly forming passion that Sciamma has been building.

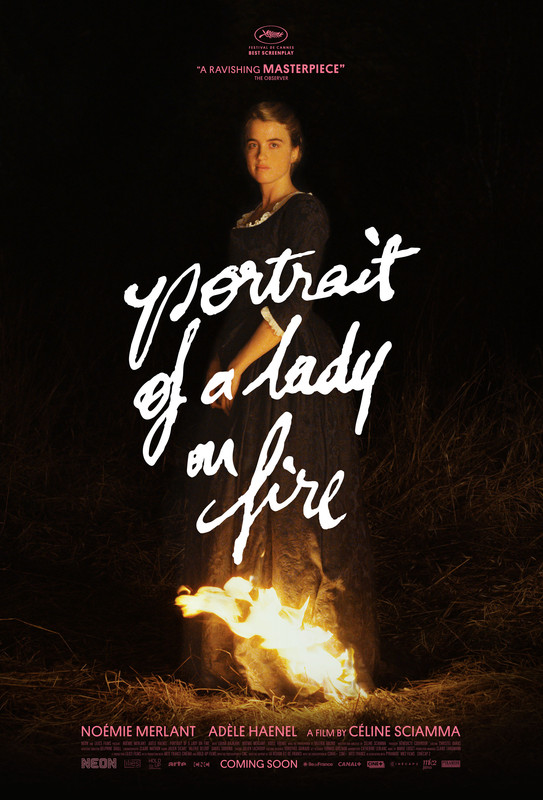

In a film where gaze is paramount, it is fascinating to watch how that aspect evolves. The connection between Merlant and Haenel changes throughout the film, and Sciamma often dwells in those moments, holding on their gaze towards each other, whether the two are in the same frame or not. The way the camera represents how they look at each other comes through in everything. It's there even in the design, the home feeling colder in the beginning of the film and the warmth of the relationship between Marianne and Héloïse seeming to warm up the surrounding environment, at least in the house, as time goes on. The central visual metaphor—Marianne seeing Héloïse standing in the opposite side of a fire at an outdoor party and Héloïse’s dress catching fire, just as the yet unspoken desire is rising on both sides—may not be subtle, but it’s evocative, thanks especially to the painterly texture of the image. This painterly feel is embedded in many of the film’s important images, most notably a recurring and fleeting image of Héloïse in a white nightgown; she seems part ghost, part painting, and that image becomes more affecting every time we see it.

The romance is the centre of the film, but many other concerns run through it as well. As well as being about love, the film features a telling depiction of female friendship and support, as Marianne discovers that Sophie is pregnant and the women try to obtain an abortion for her. That sequence, thanks to one element included by Sciamma, bears such complexity of feeling in a way that never lectures and is entirely fresh. It’s sad yet a victory; tough yet tender. Sciamma also interrogates the place of women in 18th century society. The idea that Héloïse is meant primarily as a bauble, a decoration for her husband to carry around is embedded in the portrait process, and especially in the more idealised image that Marianne paints when her model won’t sit for her. We also see this in Héloïse’s mother—clearly unhappy with her own arranged marriage, but now engaged in making the same bed for her daughter to very literally lie in.

Passionate but never exploitative, it’s obvious that a female gaze is behind the love scenes, but it’s sometimes the painting scenes that feel most telling of the relationship at the heart of the story. As they build to the first kiss, these sequences are as intense and intimate as any in the film, and after the relationship is formed they become playful; the intimacy acknowledged and embraced. Art also plays a part in the film’s most exposing scene, as Marianne draws a self-portrait, a secret thing for her lover to keep, while looking in a mirror she has set between Héloïse’s legs.

The film is exquisitely crafted, from the impeccable framing that only draws parallels between the arts of painting and cinema to the lack of non-diegetic music, which forces us to dwell in the same space as Marianne and Héloïse, to experience the growth of their love without being instructed by a score as to what we should be feeling. This extends to the work of the actresses (two men appear in the entire running time, each for a few seconds). The supporting roles are well cast, with Valeria Golino again reminding us how good she is, finding layers of sadness in the Countess and Luàna Bajrami making Sophie another interesting and important prong in the way the film looks at female relationships, beyond the romantic and sexual. Of the leads, Noemie Merlant is perhaps easier to read in the initial part of the film, from her emptiness in the opening scene to the way Marianne is progressively drawn to Héloïse, prompted initially by the mystery of what this woman may look like. The study of that face, which grows into a stronger desire scene by scene, is as brilliantly played as it is cued by Sciamma’s camera.

Sciamma has said that this film was made for Adele Haenel, and it’s difficult not to see it through the prism of their working and personal relationship. In many ways it is a film about Haenel’s face and the fascination it holds; for Marianne and, through the lens, for Sciamma. It would be tempting to take this reading further, but for all its clearly personal content there is a universality here. The power of the memory of love is hardly exclusive to any one relationship, and it’s impossible not to connect with the melancholy of that element, especially as the film runs up to the completion of the portrait. Haenel’s performance, even by her own standards, is superlative. The subtlety of what plays on her face, the way she shifts Héloïse’s character as the film goes on. She is perhaps most powerful in her silences, never more so than in the film’s beautiful final shot; a three minute take that simply tracks in on her. Haenel is one of the best female actors in Europe, and this is her finest performance to date.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire is a stunning achievement, rich and detailed in storytelling, metaphor and resonance. It’s proof that Celine Sciamma is more than just an accomplished teller of teenage stories, and further develops her cinema to put her on a level with the great visual storytellers around right now. It’s essential viewing for fans, and maybe even more so if you’ve not yet discovered her work.

★★★★★

No comments:

Post a Comment