Dir: Rupert Wyatt

I hate trailers, and Rise of the Planet of the Apes is the perfect example of why. The trailer is abysmal, first because it appears to be a three minute summary of the film (not an inaccurate impression) and second because it paints this as a dumb, shallow and frankly boring film, which it is not.

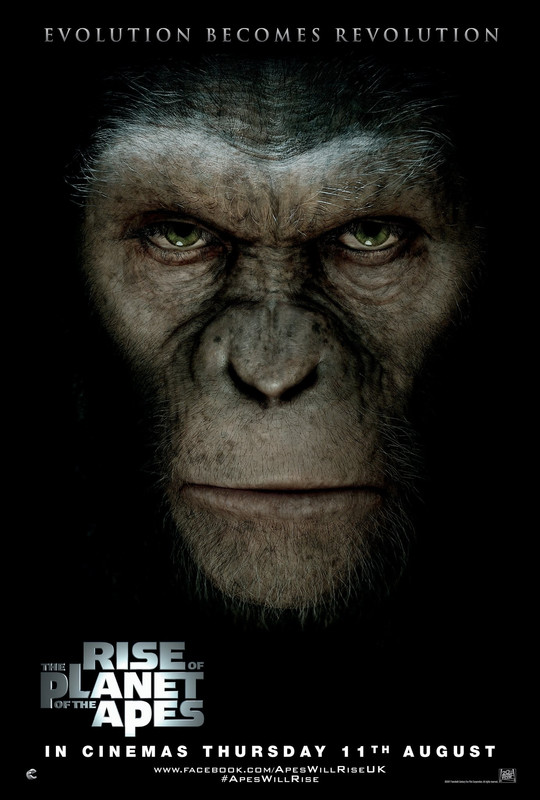

Rise draws much of its inspiration from Conquest of the Planet of the Apes; the fourth, and for me perhaps the best, in the original Apes series. However, this isn't a remake, and even that fashionable term reboot doesn't quite fit. It's just a new take on some of the ideas of the franchise, reinterpreting and updating them for a 21st century audience. Rise charts the development of Caesar (Andy Serkis, picking up where Roddy MacDowall's iconic performance left off); a Chimp born to a test subject who passed on the accelerated brain development that scientist Will (James Franco) had managed to give her in his search for a cure for alzheimer's. After being raised as a surrogate child by his creator, Caesar becomes dangerous as he protects Will's Father (John Lithgow), and is locked away by animal control. Soon, an angry Caesar begins using his advanced intellect to plot insurrection.

In an age where plot and character are becoming less and less important compared to noise and effects when it comes to Hollywood blockbuster making, Rise feels refreshing. It's a patient film, one that takes care in the development of its main character (and I don't mean Will, who is, like all the other humans, a dull cipher) and spends time developing a logically progressing plot whose stakes increase throughout. Sounds simple, doesn't it? But apparently these concepts are alien to many of Hollywood's most successful filmmakers (Yes, Zack Snyder, that's you I'm glaring at). It's also, like all the other Apes films - bar Tim Burton's botched early 2000's 'reimagining' - a film of ideas; a political piece as well as a sci-fi action movie. The ideas aren't quite as developed here as in Conquest (which is perhaps as relevant now, in the wake of the UK riots, as it was some 35 years ago), but at least there is thought and comment here, not just sound and fury.

Performance wise, Rise is something of a mixed bag. James Franco, seemingly aware that he's not what people have come to see, phones it in, which is a shame, because he's a fine actor. That said, aside from John Lithgow, who does what he can with a thankless role as Franco's alzheimer's stricken Dad, none of the humans come off well. Freida Pinto, despite her almost indecent beauty, is horribly dull; Brian Cox picks up a cheque, and Tom Felton contributes an inept American accent and a wooden performance as an eeevil animal control officer. Thank goodness, then, for the actors playing the apes. Karin Konoval and the digital team behind the Orangutan Maurice (one of several nice tributes to the original series) definitely stand out, giving the large, old, ape an imperious and melancholy presence, however, there is only one person to whom Rise belongs, and that is Andy Serkis.

Serkis has long been at the forefront of performance capture, but this is a giant step up for both actor and technology. In fact it may be the first truly seamless marriage of the two (Gollum always felt digital to me). As Caesar, Serkis has a wide range of acting challenges; he must play a wide eyed infant, an exuberant child, a rebellious teenager, an inmate and a revolutionary. Not only must he be all these things, they must all be the same thing, the same character. It's an astonishingly demanding role, but Serkis pulls it off. I say Serkis rather than Weta because, for the first time, there is a genuinely soulful feel about this performance capture character. There is physical weight and presence too; I never felt that I was watching animation laid over a performance, nor a trained animal. I was watching Caesar. He lives and breathes on screen, his eyes are alive and his facial expressions and body language speak louder than any amount of dialogue could. That is what is great, and what is remarkable, about what Serkis does here; it doesn't feel acted.

The film grows ever more intense and more interesting as it continues. It really takes off in the prison movie section (an effective analogue to that passage of the original where Charlton Heston is imprisoned by the apes). Much of this section of the film is silent, powered by Serkis and the other ape players. As Caesar's plans begin to take shape, the film becomes both moving and chilling (once in the same moment, as Caesar turns his back on his old life). The action ramps up only in the last half hour, and director Rupert Wyatt stages it effectively from both a technical and an artistic standpoint. The thick of the action is exciting, but Wyatt also knows when to pull back for a moment of quiet; a chilling shot of massed apes attacking the lab where Caesar was born, and the human army just waiting, staring at the fog, are both effective moments. The conceit of Caesar as an ape Che Guevara works pretty well, and it will be intriguing to see where the sequel takes the character, and where its sympathies will lie.

Rise of the Planet of the Apes is ultra-modern, showing off the absolute bleeding edge of special effects technology (and doing so to stunning effect), but it's also curiously old fashioned. With its 2D visuals, patient pacing, character development and political content it feels more of the Hollywood of the 70's, and that's perhaps why it's such a treat, despite the rough edges of the first, human driven, half of the film. Bring on the rumoured sequel.

★★★★☆

★★★★☆

No comments:

Post a Comment