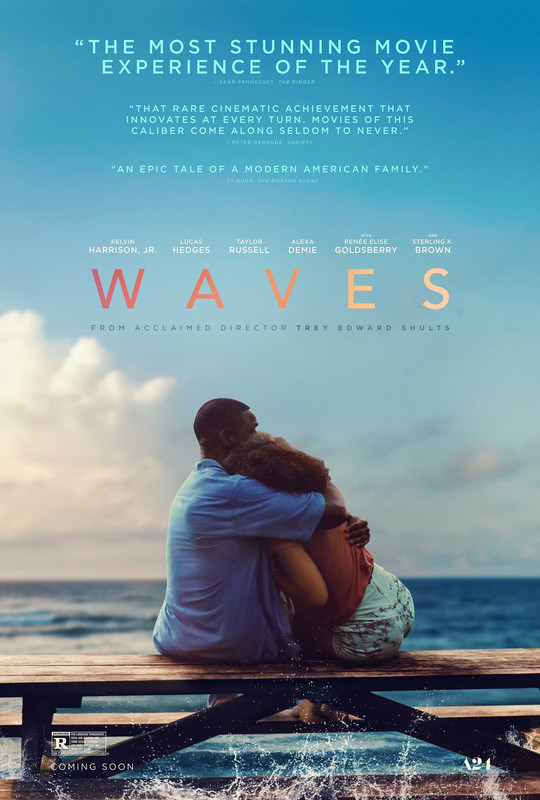

Dir: Trey Edward Shults

Writer/Director Trey Edward Shults impressed me with his second film, the low-key horror inflected family drama It Comes At Night. His third, as its title might suggest, is bigger and more expansive, yet it remains focused on the small dramas of a family in Florida, dramas which sometimes boil over into life altering moments.

Tyler (Kelvin Harrison Jr) is from a solidly middle class family; a good student, wrapped up in his beautiful girlfriend Alexis (Alexa Demie), and a star on the high school wrestling team. He’s also often under pressure from a demanding father (Sterling K. Brown) and a combination of injury and unexpected news begins to send him off the rails. In the second half of the film, Tyler’s sister Emily deals with her own pain and guilt through a relationship with one of Tyler’s teammates, Luke (Lucas Hedges).

Waves are unpredictable and, like its namesake, this film moves in different ways through its 135 minute running time. At times, it crashes relentlessly; all furious noise and violent emotion, in other moments it gently rolls; time passing in something like a distracted haze. Shults balances these different moods beautifully. He evokes them through the use of his camera, for instance, the endless spinning of the opening sequence throws us into the noise of the lives of its young protagonists, while the off balance stalking quality of a sequence at a party strikes a note of foreboding that turns Waves into a horror film for about ten minutes. The shot composition is often masterful, and called particular attention to by the shifting aspect ratios which move us between the acts. The first of these is especially striking, as in one instant a single act metaphorically shrinks the world in which Tyler, and consequently his family and friends, exists, sending the film into 4:3 ratio. The ratio continues to shift throughout the film. Remarkably, Shults manages to do this without it feeling trite, rather each time it happens - always preceded by a brief blackout - the film is taking a breath and resetting; into panic as walls instantly close in the first instance, and later to a more expansive experience and finally back to the sure footing of the first ratio we saw. It becomes a key part of the film’s emotional journey, both for the characters and for us.

While Shults’ visual craftsmanship is often what commands the attention, it is underpinned by some outstanding performances. Sterling K. Brown plays Tyler and Emily’s father as a man we are given to believe has pulled himself up through hard work, and is sometimes too tough on his son in his desire to bring that same commitment out of him. This toughness is what we see for the bulk of the first act (which takes up the first half of the film), but the second and third reveal it as a shell that can be cracked, in some of the film’s most emotionally wrenching scenes. Good as Brown and Renée Elise Goldsberry (as Tyler and Emily’s stepmother) are though, this is largely a coming of age story, and as such it centres on the younger actors. Kelvin Harrison Jr gives a performance of building resentment as Tyler’s denial about his terrible shoulder injury builds and his anger at his father and at his girlfriend; one for pushing him too hard the other for, in his mind, pushing him away. It would be easy to hate Tyler, but the film establishes him initially as a nice kid, we can understand if not sympathise with his denial and his rage - at least towards his injury - up to a point. The final moments of the first act are brutal; a momentary act that echoes throughout the film and will do for all the characters long past the credits, and the second, third and fourth acts all ask us to dwell in the aftermath of that act from an angle we don’t often see. Harrison is outstanding in the part, the pressures Tyler feels and the sense of loss at what to, whether it’s to avoid disappointing his dad or to win back Alexis, is always at boiling point inside him.

The second half of the film, broken into its last three acts, largely turns the focus on Emily and on her budding relationship with Luke. Taylor Russell and Lucas Hedges establish a warm and naturally growing chemistry, begun with a perfectly awkward scene of Luke asking Emily out, which seems designed to play as the direct antithesis of Tyler and Alexis’ fast burning and eventually angry story. This is certainly a more typical coming of age story than is presented in the first half, but it too is suffused with the striking colours and inventive camerawork that Shults brings to the telling. Russell and Hedges are both wonderful, and it’s the first time I’ve really bought into the hype around Hedges. That said, the standout scene of the second half isn’t between them but between Russell and Sterling K. Brown, as Emily and her father finally talk about the emotional fallout of what happened with Tyler and Alexis.

Waves isn’t perfect. Shults’ Malickian shots of people leaning out of car windows and his colour wash transitions can feel a little self-indulgent at times, and much of the final section of the film is spent on a storyline that has barely been seeded and feels like a digression from the main thrust of the film. However, if the film doesn’t hit the bullseye on every emotional target it takes aim at, those it does strike resonate powerfully and for a long time.

★★★★

A great, detailed review. I am still digesting Waves after watching it yesterday as it is so rich in material and settling. The cinematography and the score are very impressive and reflect that shift in tempo within the film's structure. It would be good if the film receives the recognition it deserves!

ReplyDelete