Dir: Atom Egoyan

There has been no criminal case in recent memory as extensively covered in the media or whose coverage has had a greater effect on its proceedings than that of the West Memphis Three. Three eight year old boys were gruesomely murdered and three misfits in their mid to late teens (Jason Baldwin was 16, Jessie Misskelley 17 and Damien Echols 18) were subsequently convicted of the crimes. That might have been the end of the story but for an HBO documentary crew, whose film Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills won acclaim and helped establish an activist group, Free The West Memphis Three, who spent years trying to draw attention to the flimsiness of the evidence on which the three were convicted. The movement grew, creating endless news coverage, and the appetite for more information on the case led to two more entries in the Paradise Lost series, a further documentary titled West of Memphis and a book called Devil's Knot, by Arkansas journalist Mara Leveritt, which has now been adapted into this, the first non documentary narrative film about the case.

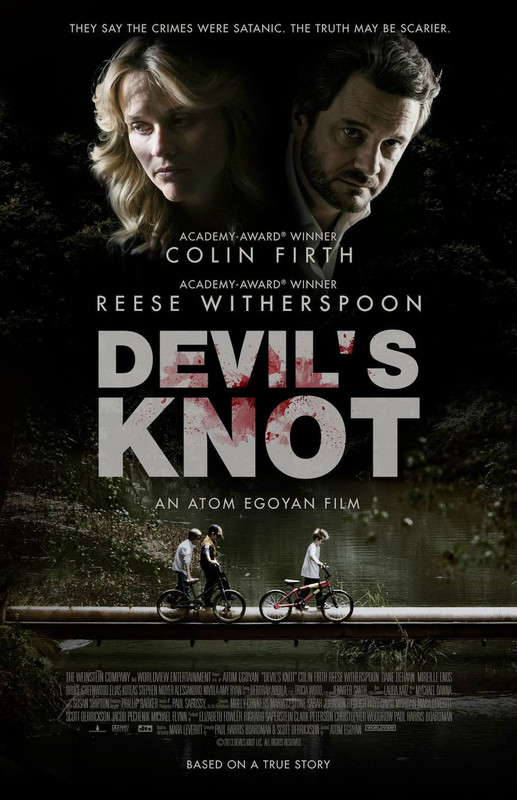

With so much having already been said on the case you could be forgiven for thinking that there is little or nothing left for director Atom Egoyan to explore. In reading Devil's Knot I saw that this isn't the case. There are many narratives in Leveritt's book that have not been delved deeply into by the films to date, and many viewpoints to take that we have not yet truly seen this case through. Egoyan takes none of them, instead opting for a straightforward, surface level, telling of the investigation and initial trials (Jessie, who gave a heavily disputed confession, was tried apart from Jason and Damien). Though he does heavily feature a figure who is not that present in Paradise Lost, defence investigator Ron Lax (Colin Firth), Egoyan is completely hamstrung by the documentary, shackled to its events, often restaging moments in a series of scenes that come off as cheap tragedy karaoke.

When the real story would allow him to do something interesting with a restaged scene, Egoyan resists. For instance, on the Paradise Lost commentary directors Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky recall filming a news crew while they filmed an erratic interview with Pam Hobbs (Reese Witherspoon), the mother of one of the murdered children. They also recall that afterwards they got her a hotel room, giving her a place to pull herself together and generally taking care of her. They asked her no questions and did no filming at that time. This is an interesting angle; one that we've never seen on screen and, given that Pam is the other main character, it might be an instructive moment to see and give us a real insight into her at that moment and into what was happening around her. Instead, Egoyan simply has Witherspoon restage the moment. Given that Witherspoon looks credibly like a Hollywood pretty version of Pam Hobbs it has the effect of seeming as though the documentary has been airbrushed.

This sense of the airbrushing of history also comes through in the film's impact. Paradise Lost and West of Memphis may not be perfect films, but they hit like a punch to the gut. When Jason's lawyer cross examines an occult 'expert' during the trial in the documentary you feel how completely he destroys the man's credibility. In Devil's Knot much less time is given to this moment and its impact is greatly reduced. This issue of time is one the film struggles with constantly, at 110 minutes it has to race through the year and a half over which the story is set. Mawkish and inessential scenes with Pam (an abysmal one in which she goes to see her son's teacher and get his last piece of homework marked, for instance) and Lax (a one scene cameo for Amy Ryan as his ex wife) take time away from the case itself. This means that when the film introduces elements that the documentaries left room to develop further, particularly characters played by Dane DeHaan and Mireille Enos, it has to rush through their parts in the case. This leads to laughably broad moments like Enos' Police 'informant' meeting Damien and Jason for the first time and continues the general problem of important moments simply lacking impact.

There are plenty of ways in which Egoyan and writers Paul Harris Boardman and Scott Derrickson could have avoided these pitfalls. Why not focus more closely on the Police investigation and the specifics of how it was botched? We've never seen the story from that point of view. This would also have boosted De Haan and Enos' roles in a way that would lend more weight to a less explored side of the story. Or the film could have gone in the other direction and elected to use the West Memphis Three's prison lives, which, again, little has been written about aside from Damien Echols' memoir, as a jumping off point to flash back and fill in the case. This would also have had the virtue of avoiding the trap that Egoyan, Boardman and Derrickson fall into of making the WM Three bit players in their own story.

Egoyan's direction is perhaps the least distinguished and least personal he has ever committed to film. Often it seems as though he is simply repositioning Berlinger and Sinofsky's documentary cameras and when that's not the case he over-dramatises a story that has plenty of feeling inherent in it. I wonder how Pam Hobbs feels about this film, because nothing I have read or seen suggests that the doubts her character seems to have about the WM Three's guilt from about halfway through the trial (largely played in significant shots of Witherspoon frowning a bit) actually came about until ten or twelve years after the convictions. Watched with a knowledge of the case this plays not as a realistic emotion but as a sop to Hobbs' current beliefs on the truth of the case. In the bulk of the film Egoyan's images are purely functional and rather dull and his few directorial flourishes (a dream that Lax has, an Esbat) are laboured at best and irrelevant at worst. This is all the more disappointing from a filmmaker who once made The Sweet Hereafter, which speaks movingly about the effect of tragedy on a community.

Everyone seems reduced by the weight of this project (which, ironically, renders it featherlight and disposable). Witherspoon goes for broke for another Oscar in a couple of early scenes before spending the film's second hour looking concerned and upset in the background. Firth seems lost, miscast as Ron Lax, who lacks any real traits beyond honest to goodness decency. The rest of the cast end up as a parade of faces who either plunge you into or extract you from uncanny valley, depending on how much they look like their real life counterparts. Matt Letscher and Michael Gladis are especially eerie as defence lawyers Paul Ford and Dan Stidham, while Kevin Durand is distractingly inexact as John Mark Byers, who has always been the most visible of the bereaved parents in the case.

Devil's Knot is a film made infinitely worse by its inevitable association with what has gone before it, but even if you've not seen or read anything about the case before, even if you don't know the background, it's a bad film. Egoyan and his actors flounder. They try to relate an important and hard hitting story, but race through an incomplete and unsatisfying telling. I would be amazed if newcomers can follow it (despite the reams of captions before the end credits, covering the 18 years after the film's events) and even if they do they will likely come out seeing this as a much less interesting case than in fact it was. That's the biggest crime perpetrated by this film; it makes a story that has, so far, gripped people for 21 years boring.

★

★

No comments:

Post a Comment